The marine station at Villefranche-sur-Mer, once an eighteenth century naval base, bathes in the light of the Mediterranean. I’ve returned from a very good conference there a week or so ago. Perhaps the most interesting part was a brief but intense debate I’m still thinking about, which concerned development in animals.

The marine station at Villefranche-sur-Mer, once an eighteenth century naval base, bathes in the light of the Mediterranean. I’ve returned from a very good conference there a week or so ago. Perhaps the most interesting part was a brief but intense debate I’m still thinking about, which concerned development in animals.

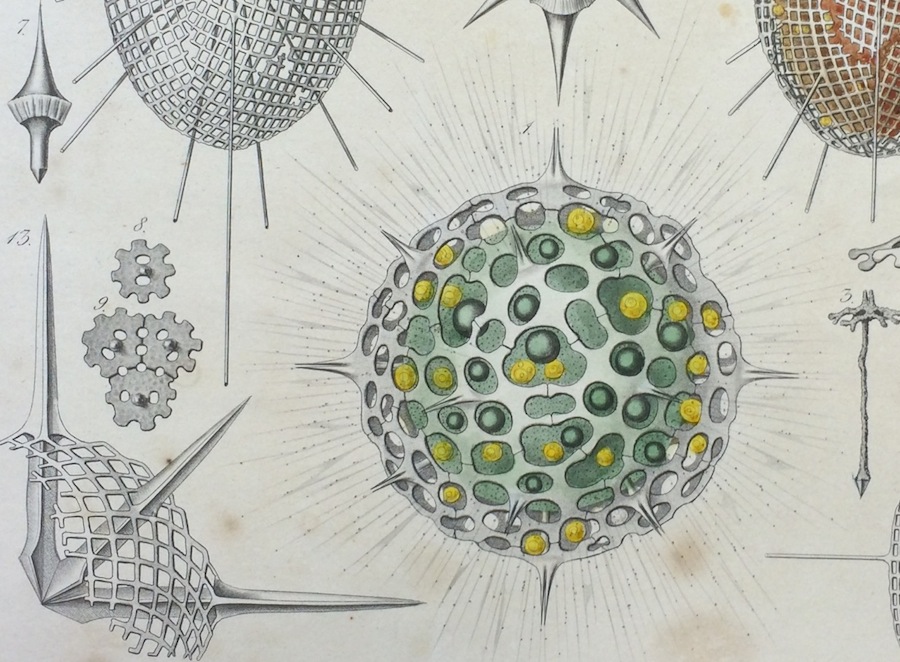

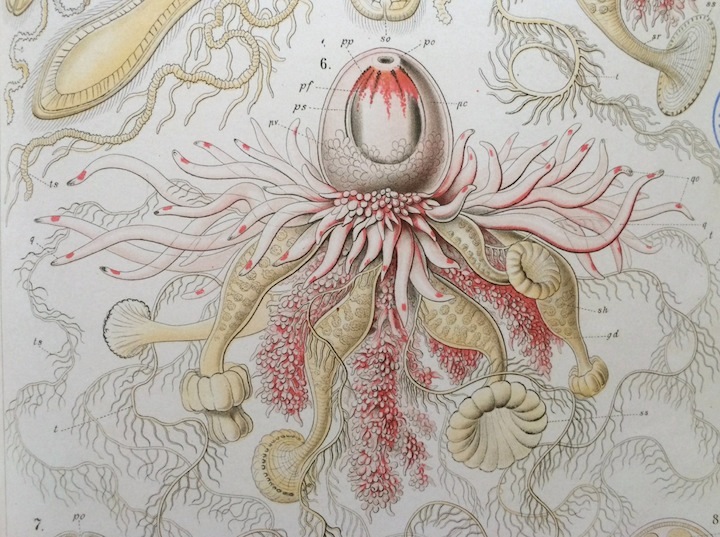

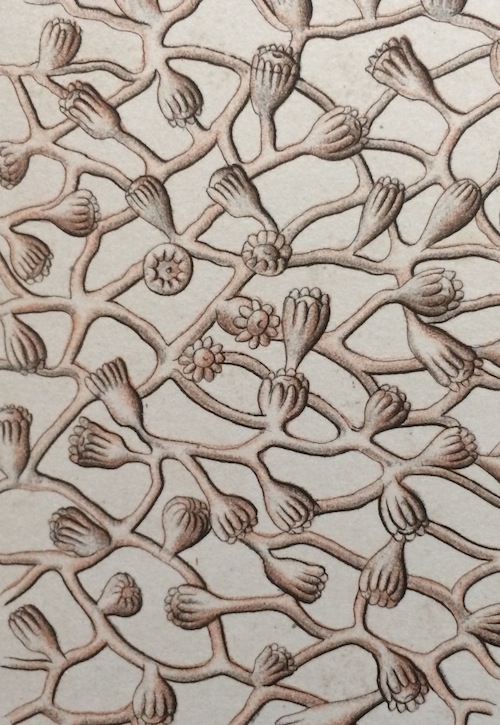

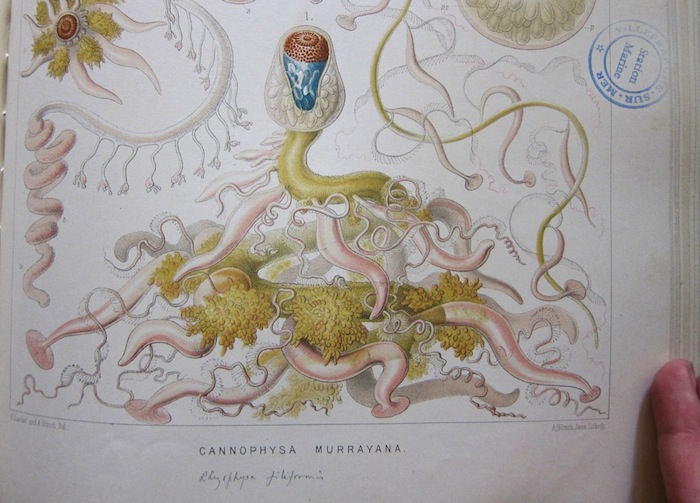

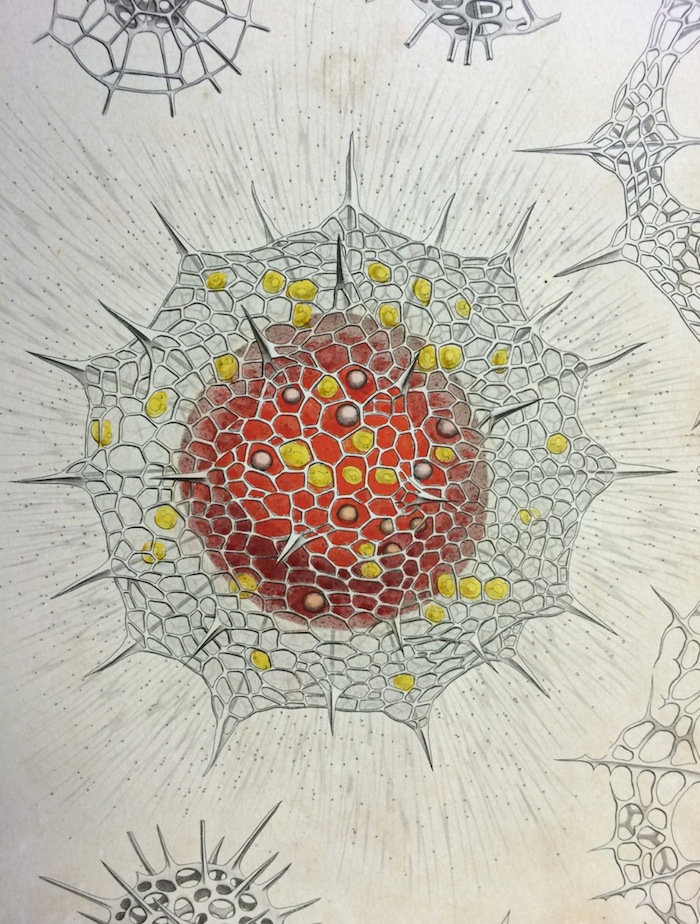

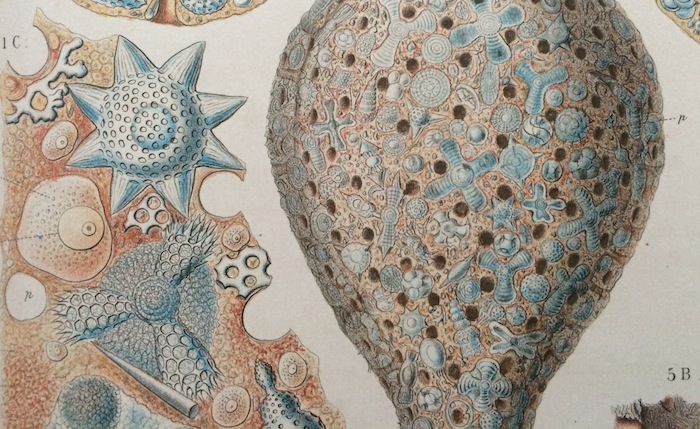

We also spent some time in the library, which has a complete set of the “Challenger” volumes, the fruit of a 1872-1876 expedition that pioneered oceanology. The HMS Challenger, a converted British navy ship, roamed much of the world sampling life in the deep sea. They didn’t use a diving bell or anything similar, but hauled samples from different depths and locations on board, catalogued and studied them. All the images in this post, except for one, are snapshots of plates from the Challenger volumes. Seeing the rows of green-spined books together, I was struck by what a monumental amount of work went into the project, what an achievement it was.

The different groups of organisms were handled by specialists, writing long, patient descriptions and preparing figures. About 4000 new species were found on the voyage. Several groups were given to Ernst Haeckel, the German biologist and illustrator known now especially for his 1900 book Art Forms in Nature. I’d never seen original plates of Haeckel’s before, and they are indeed stunning.**

Here is a sample of discussion at the conference. There’s currently a push in much of biology towards recognition of the importance of symbiotic relationships, especially cooperative relationships that large organisms like ourselves have with bacteria and other microbes. Sandie Degnan gave a talk about sponges. The sponges she studies house a large and shifting population of bacteria, some of which are essential to the sponge’s metabolism. Some of the bacteria are also “vertically” transmitted; the embryos receive a sample of bacteria from their mother sponge while in a “brood chamber” before release into the sea as larvae.*

These are tightly integrated symbionts. Part of the aim of Sandie Degnan’s talk, though, was to ask some questions for those revisiting issues of “individuality” in the light of symbioses of this kind. Some people think that the organism, in a case like this, is a combination of animal parts plus microbial parts – not just the animal. Degnan asked: what about cases where the microbial population within an animal changes a lot over the animal’s lifespan? If there is not a stable community of internal microbes, but a shifting one, does this affect the idea that the organism (which we think of as having a single life) is made up of both parties? That’s an interesting question, but not the one I’ll focus on here.

These are tightly integrated symbionts. Part of the aim of Sandie Degnan’s talk, though, was to ask some questions for those revisiting issues of “individuality” in the light of symbioses of this kind. Some people think that the organism, in a case like this, is a combination of animal parts plus microbial parts – not just the animal. Degnan asked: what about cases where the microbial population within an animal changes a lot over the animal’s lifespan? If there is not a stable community of internal microbes, but a shifting one, does this affect the idea that the organism (which we think of as having a single life) is made up of both parties? That’s an interesting question, but not the one I’ll focus on here.

In the last talk at the conference, Thomas Pradeu looked at the role of symbiotic associations in development – the change an organism undergoes from embryo (or similar) to adult. He set things up like this. Developmental biology is the part of biology that has been most attached to an “internalist” view of organisms – development is seen as the unfolding of inner potentialities, or the expression of a genetic program. He argued that even here there’s an essential role for symbiotic associations, with bacteria often playing a role in triggering and controlling the developmental process, including in mammals like ourselves. Animals are constructed through “developmental symbiosis.”

At this point, people began to object. Symbiosis is important, but that is going too far. The objectors included me – cautiously, as I’m not a developmental biologist – and Bernie Degnan. Putting together points made by a couple of people, the challenge went like this. Symbiotic associations may well be important in prompting and modifying lots of events in biological development, but that’s compatible with it being a minor player. It might not touch the heart of the matter, which is the establishment of an animal’s body-plan – its axes of symmetry and the layout of its main parts. The mainstream view, which Pradeu was criticizing, holds that those features are generated by genetically orchestrated cascades of internal signals. This process is supplemented by triggers and prompts from outside, but that – again – is the easy part. Once a body plan is in place, there can be all sorts of modifications, fine-tunings, and add-ons, many perhaps affected by symbiotic associations. But those are secondary – icing on the cake – and should be distinguished from the central phenomena, which are orchestrated internally.

At the beginning of animal evolution, associations between eukaryotic cells and bacteria may also have been essential in setting things in motion. (Nicole King, at Berkeley, has developed a hypothesis of this king.) But in the years since then, animal cells built, and came to inhabit, an internal logique of cell-to-cell interaction.

The debate continued – with replies and replies to replies – but I’ll leave it there for now. I may also write about some other Villefranche talks in a later post.

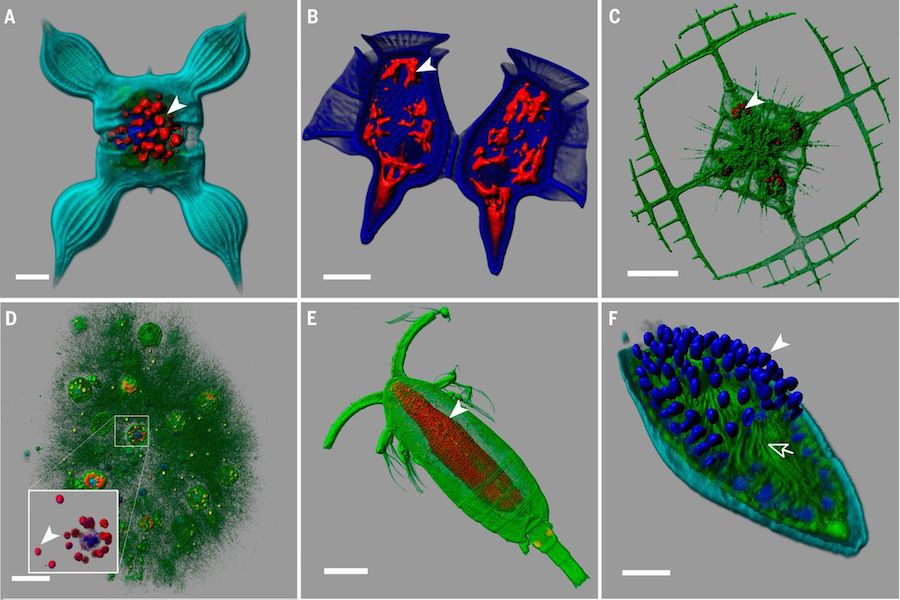

The Villefranche Station was also one of the labs involved in the Tara expedition, completed just a few months ago. Tara, a worldwide study of the ocean’s plankton, has been compared to the Challenger expedition in its scope. The work was celebrated in a Science Magazine cover in May, a review article from that issue is here, and a New York Times article is here. Below, from the review, is a 21st century analogue of a Challenger plate. The colored patches show symbionts, and remnants of symbionts, inside other tiny organisms. Pradeu should be pleased.

________________

* The sponge is hermaphroditic. Sperm are broadcast into the sea (“spermcast mating”), and taken up by adult sponges to combine with their eggs, which are brooded, bacterially supplemented, and then released as larvae.

** All the Challenger images here are by Haeckel. The first two organisms are radiolarians, followed by a deep sea sponge with radiolarians and other organisms embedded in it, followed by various cnidarians.

Wandering around the web I saw several references linking Haeckel to national socialism and anti-semitism. The historian Robert Richards has written a critical assessment of this alleged connection.

Thanks to Evelyn Houliston, Lucas Leclère, and everyone at Villefranche.