The epigraph to Metazoa is a passage from Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick. The narrator, Ishmael, is describing the task of watching for whales from high on a mast. “Let me make a clean breast of it here, and frankly admit that I kept but sorry guard.” His poor performance, he says, was due to his being distracted by “the problem of the universe.” He then gives some advice to shipowners: “Beware of enlisting in your vigilant fisheries any lad with lean brow and hollow eye; given to unseasonable meditativeness; and who offers to ship with the Phaedon [by Plato] instead of Bowditch [a handbook of navigation] in his head.”

And then:

“Why, thou monkey,” said a harpooneer to one of these lads, “we’ve been cruising now hard upon three years, and thou hast not raised a whale yet. Whales are scarce as hen’s teeth whenever thou art up here.” Perhaps they were; or perhaps there might have been shoals of them in the far horizon; but lulled into such an opium-like listlessness of vacant, unconscious reverie is this absent-minded youth by the blending cadence of waves with thoughts, that at last he loses his identity; takes the mystic ocean at his feet for the visible image of that deep, blue, bottomless soul, pervading mankind and nature; and every strange, half-seen, gliding, beautiful thing that eludes him; every dimly-discovered, uprising fin of some undiscernible form, seems to him the embodiment of those elusive thoughts that only people the soul by continually flitting through it. In this enchanted mood, thy spirit ebbs away to whence it came; becomes diffused through time and space; like Wickliff’s sprinkled Pantheistic ashes, forming at last a part of every shore the round globe over.

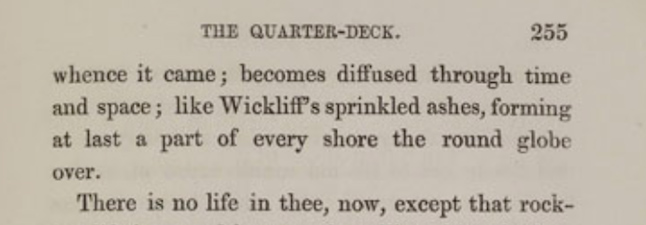

There is a story behind this passage, and quite a tangle of lines and rigging. The copy of Moby-Dick I usually read is a facsimile of the US first edition. In that edition, the name near the end of the passage is “Cranmer,” not “Wickliff.”

Curious about him, I did some reading. Cranmer was an important figure in the English reformation, Archbishop of Canterbury during the reign of Henry VIII and after (he appears from time to time in Hilary Mantel’s famous “Wolf Hall” novels). From an annotated online Moby-Dick, I learned that the first edition of Moby-Dick actually printed, the UK first edition, had “Wickliff” in this passage, not “Cranmer,” and this looks like a correction. The story with the sprinkled ashes fits John Wycliffe well, not Cranmer. Wycliffe was an earlier English religious reformer, a sort of proto-protestant, who died in 1384 of natural causes. In 1415, however, he was declared a heretic and the Pope ordered his remains removed from consecrated ground. Those remains were burned and his ashes thrown into the River Swift.

Cranmer, in contrast, was executed by burning in 1556, on instruction of Queen Mary I, and the details of his death, while famous, have no particular role for the sprinkling of ashes.

The version of Melville’s text with Wycliffe substituted for Cranmer appeared in the England before the US edition, but this English version had corrections added while the uncorrected US edition was still in press.

Who actually made the correction, though? For reasons outlined further below, I eventually got in touch with a Melville expert, John Bryant, and asked him about all this. I could not have chosen a better correspondent. Bryant filled in the many-layered story (some of which is also online here).

Publishing a book separately in both the UK and US was an anti-piracy maneuver. Melville sent to London a set of proof sheets of the book, after it had been typeset in New York. Melville made some changes to the text on those sheets, and then his English publisher, Richard Bentley, made hundreds of additional changes, removing all sorts of material on sexual and religious grounds, and dropping the Epilogue that records Ishmael’s survival. So as Bryant discusses in detail in his own work, Moby-Dick is a “fluid text,” one that exists in several versions. Bryant and others believe that the change from Cranmer to Wycliffe, unlike many other edits, was probably made by Melville himself. The US version with its uncorrected “Cranmer” came out about a month later – Melville was not able to make any corrections to that version. The Norton critical edition of Moby-Dick includes the correction.

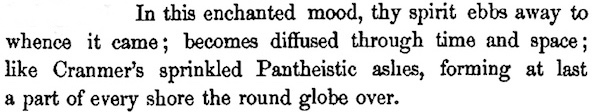

I am jumping a little ahead, though. When I learned about the Cranmer-Wycliffe issue, I followed the correction and changed to “Wickliff.” Then during the proof-reading process for Metazoa, I did a more detailed check of my epigraph passage against the UK edition, given that I was using its revision of the ash-sprinkling. This book is hard to find. I eventually used photos of the pages here. There I saw that in the UK edition, the word “Pantheistic” does not appear; there, the phrase reads “Wickliff’s sprinkled ashes.” There are also a few minor changes to the punctuation in the UK version, some of which help make the passage clearer.

So the UK has Wickliff’s sprinkled ashes and the US has Cranmer’s sprinked pantheistic ashes. Which edition has Wickliff’s sprinkled pantheistic ashes?

That is the question I wanted to ask an expert, and why I got in touch with John Bryant. He explained that this phrasing was put together only in later critical editions – the Northwestern/Newberry edition and then the Norton. Most other editions of Moby-Dick tend to follow this decision – you will usually see Wickliff’s sprinkled pantheistic ashes.

The reasoning behind this wording might be something like this. It seems widely agreed that Melville did intend the correction of Cranmer to Wycliffe, but it’s not clear that he meant to drop “Pantheistic.” The UK editors made many changes on religious grounds. So the word might be restored.

The result is that the most standard version of this passage uses a wording that appears in none of the original editions and may never have been intended by Melville. That is what John Bryant thinks; he suspects that the cut of “Pantheistic” was probably Melville’s own correction, in part because the word “Pantheists” appears again soon after, and the repetition is a bit awkward. In the alternative scholarly edition, with Longman, that Bryant co-edited with Haskell Springer, they opted for “Cranmer’s sprinkled Pantheistic ashes,” along with a detailed explanation.

That left me with three options for the ashes: Cranmer’s sprinkled pantheistic, Wickliff’s sprinkled, and Wickliff’s sprinkled pantheistic. My preference was to go with the third, despite the controversy. My editors at Farrar, Straus & Giroux also thought that the Norton precedent was important, as that edition has become standard. The other option was to stick to the US edition, and explain its apparent error in an endnote. But explaining it in that direction made the note into a mess, and it seems so clear that “Cranmer” was simply a mistake. Indeed, while reading more about Wycliffe, I happened across this passage in an old church history:

They burnt his bones to ashes and cast them into Swift, a neighboring brook running hardby. Thus this brook hath conveyed his ashes into Avon, Avon into Severn, Severn into the narrow seas, they into the main ocean. And thus the ashes of Wicliffe are the emblem of his doctrine, which now is dispersed the world over. (Thomas Fuller, The Church History of Britain, 1655)

The Melville passage echoes the last phrase of Fuller – “the world over”/“the round globe over.”

I am no expert on Melville, or Church history, or nineteenth century editing practices, but for what it’s worth, I do wonder whether the deletion of “Pantheistic” in the UK edition was one of those religiously-motivated edits. Wycliffe’s own relationship to pantheism is interestingly unclear. Some things he wrote seemed to tend in this direction, but he is said to have rejected the doctrine.

The realism of Wycliffe comes to light with especial clarity in his doctrine of God the Son as the Logos, who as the essential Word is the summation of all ideas, that is, of all intelligible realities. Such pronouncements as the following result: “Every creature (thing created) that can be known is the word of God in relation to its intelligible being and therefore in relation to its essential being; every being is in fact God himself.” Although these and other declarations aim at a monistic doctrine, Wycliffe declined to accept pantheism. In this respect he was a follower of Augustine. (source here)

Given this, it does seem possible to me that a religiously minded English editor might delete “Pantheistic” when Wycliffe was brought in for Cranmer.

So every version of the passage is questionable: the US errs with Cranmer, the UK deletion of pantheism is questionable, and Norton publishes a phrase that appears in none of the original editions. I went with the Norton wording, as I say, because Cranmer is clearly an error that I couldn’t handle well with a note, also because the link to pantheism is an important part of the sense of the passage as I use it here – this second reason is not a scholarly argument at all, but one concerning my own goals with the text – and because I am not at all sure that the UK editors wouldn’t have removed “Pantheistic,” given that they were willing to remove all sorts of religiously controversial passages from Melville’s original.

________________________

Many thanks to John Bryant for his generous help with this problem. His new multi-volume biography, Herman Melville: A Half Known Life, is coming out in stages. The first two volumes, just released, cover the early years through to Typee.

In the Audible version of Metazoa, the Melville epigraph (along with James and Proust) is read by the vocal artist Mitch Riley.

Fascinating. It’s good to read an exploration of these esoteric links between literature, philosophy, and science. And it makes me want to re-read Moby-Dick.

Thank you.

And yes, it’s always good to go back and dive again into Moby-Dick.