I wrote a post in September about a trip we made to two octopus sites, Octopolis and Octlantis in Jervis Bay, back in February. Octopolis was very quiet, with just two or three octopuses in residence. Octlantis had more going on, with five on-site, another nearby, and a couple of notable behaviors. This post is about the behaviors.

The main video I want to show is here:

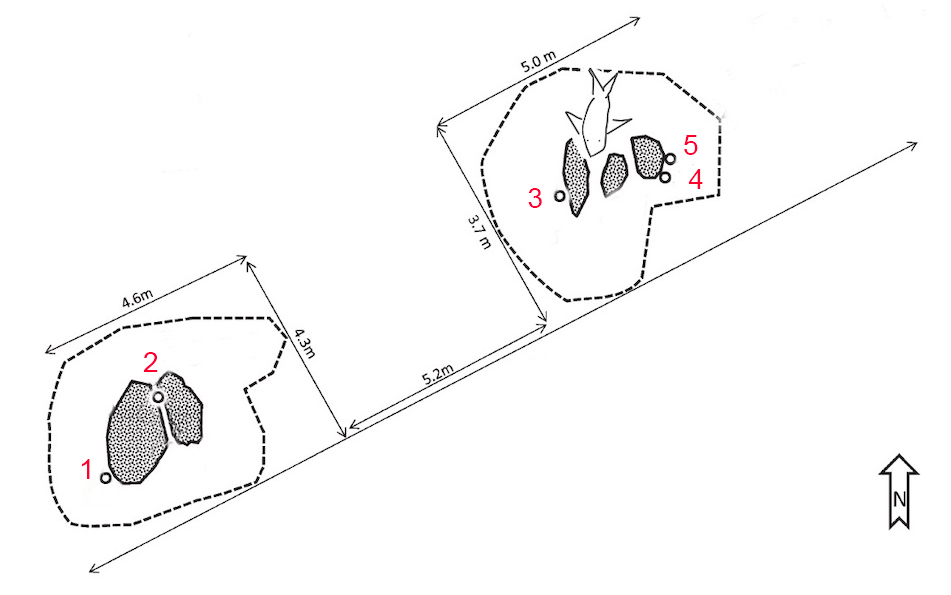

This octopus is making its way from one end of the site to the other, in an apparently targeted manner.* In this map –

– the octopus starts as the octopus in position 1, and ends up visiting Octopuses 4 and 5. The distance is about 12 meters, and his path looks quite direct. He does make a sideways adjustment at the very end, as you can see. (The map is modified from one drawn for our main paper about the site.) As I said in the previous post, this suggests that octopuses at the site do, at least sometimes, have a good idea of who is present all over the site, including areas on the other side of the sand gap. The movement of the octopus is also a nice case of “moving rock” locomotion. The reason for the name is obvious. David Scheel mentioned four species to me where the behavior has been reported – Octopus vulgaris, cyanea, rubescens, and Abdopus aculeatus. The new edition of Roger Hanlon and John Messenger’s classic Cephalopod Behavior (2012) has photos with some others – Octopus burryi, and also Octopus tetricus. So it’s not a new observation for this species. It’s a nice example, though, and I don’t think I’d seen as clear case like this in our local octopuses before.

When the moving rock arrived, he approached Octopus 4 and got into a brief fight with Octopus 5. He evicted Octopus 5 and then attempted to mate with Octopus 4. Here’s the second part of the video, with the eviction –

The eviction has another notable feature. At the rock’s arrival, Octopus 5 darkens and raises his mantle over his head (“his” because this one is very likely to be male). This is around 10 to 12 seconds in. This pose with a darkened body and raised mantle is one that we interpreted, in an earlier paper, as a signal of aggression. A brief fight does ensue in this case, and the fight is initiated with a lunge by Octopus 5. The pose is like a brief and partial version of the “Nosferatu” pose. Octopus 5 does not raise his whole body up and spread his web, but the mantle-over-head and dark color do fit that pattern. It has been suggested to us that the raised mantle is not really a signal, but just a preparation to jet. In this case, there is nowhere to jet (except away) and that is clearly not the point of the behavior. Octopus 5 has encountered an intruder and his options are to fight or retreat. He fights, and the color and pose are a prelude to the fight. When he gives up and retreats, he goes into a paler, mottled pattern. Here he is, from the video, with the dark colors and raised mantle:

I don’t have an interpretation of the colors on the formerly moving rock.

After the moving rock octopus had evicted Octopus 5, he attempted a mating with Octopus 4.

He spent about 5 minutes with his mating arm extended, without much reaction. In the very last photo I took at close range, a couple of minutes after this one, it looks like the female was accepting the mating.

______

Thanks to David Scheel (who sent helpful thoughts on this post, as well as all the rest), and to Matt Lawrence, Marty Hing, Kylie Brown, and Zoe Munson.

Octlantis is within beautiful Booderee National Park. Many thanks to the custodians of the park, the Wreck Bay Aboriginal Community.

* The site used to have one other patch of inhabited rocks, a bit to the north east. That part has disappeared. See our earlier paper.