This post is an update of what has been happening, as far as we know, at Octopolis and Octlantis, the two high-density octopus sites that I’ve been watching for over a decade now.

The Octopolis site, in Jervis Bay, Australia, was discovered by Matt Lawrence in 2009. Octlantis, which is fairly close by, was discovered by Marty Hing and Kylie Brown in 2016. (The name “Octlantis” was coined by Stephanie Chancellor; “Octopolis” was my term.) The last time we did real data collection at the sites was back in 2018. We didn’t visit at all during Covid, and the couple of years since then have been bad diving years due to storms and floods. Matt Lawrence has dropped in a few times, and said that Octopolis was very quiet. Back in February of this year we went back for a proper look at both sites. Matt and I were joined by David Scheel and Zoe Munson from Alaska, and Marty and Kylie the Octlantis discoverers.

Octopolis was indeed quiet. It had two or three octopuses (a possible one well-buried) on the main site, and another just outside. The octopuses were sitting quietly (though the one above was rearranging, probably not waving, a shell or two). Given the size of the site (an oval of 2 x 1 meters or so), that number is not notable for density.

I spent a bit of time on that first dive following a couple of nudibranchs of the Armina genus, with their characteristically purposeful crawl, and photographing a less common animal – a sapsucking slug (Stiliger smaragdinus I think, and the head is on the left).

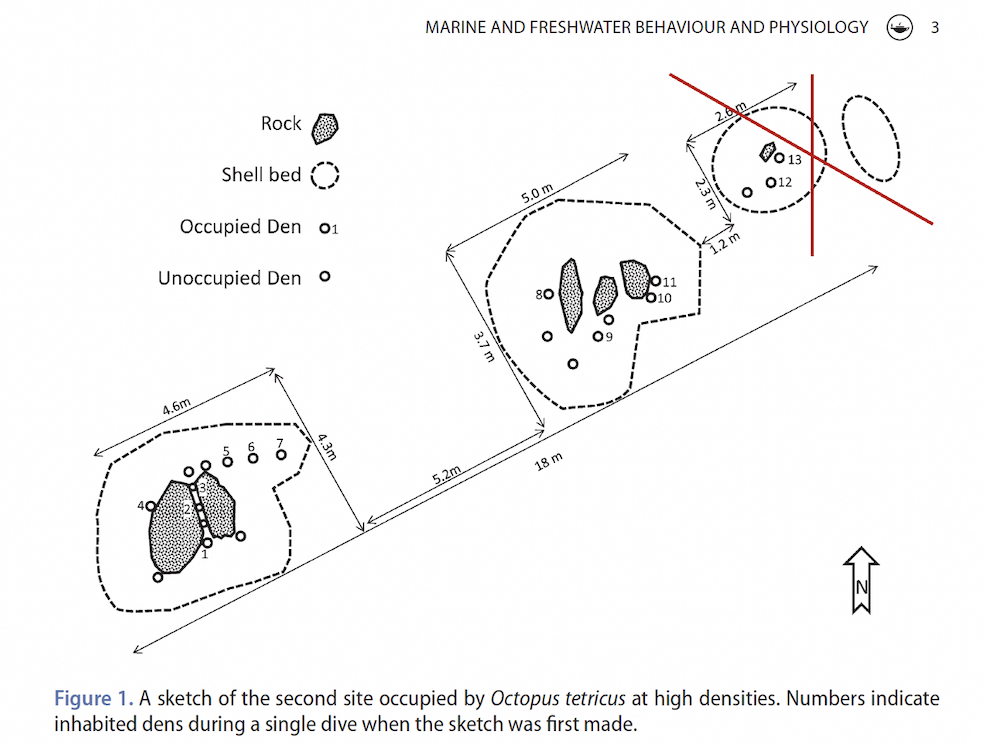

Octlantis was a different matter. There were five octopuses on the site, and another (who I did not see) nearby. Below is a map from our first paper about the site, when 13 octopuses were present. Five is a lot less than that, but the site had some interesting activity, and the visit was notable for two behaviors I saw.

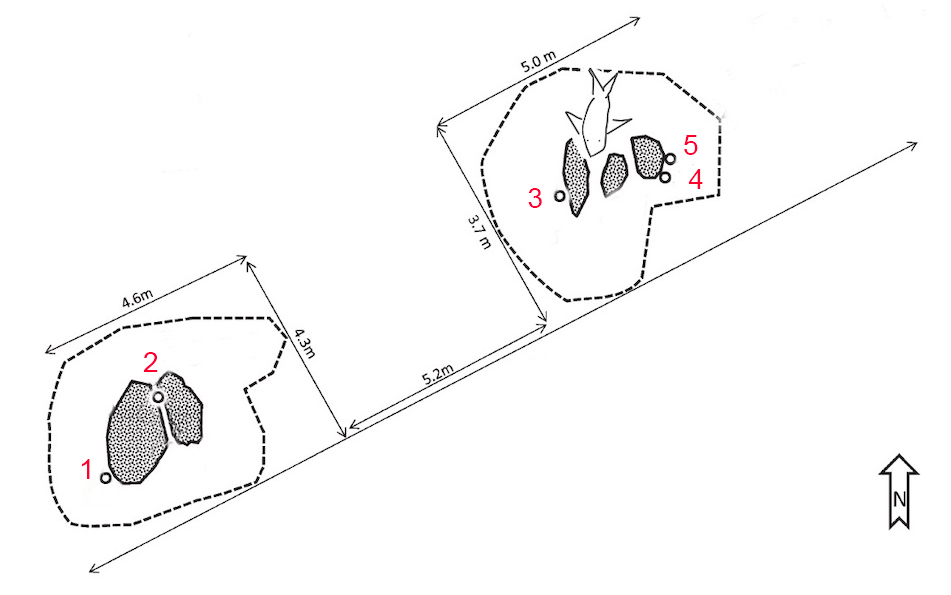

As marked in red above, the far north-east part of the site had disappeared in February – no octopuses and not much of a shell bed. All three parts of the Octlantis site have some rocks protruding from the sand, and the octopuses tend to make dens at edges and cracks between these rocks. The map below marks who was around in February.

Octopus 1, on the western edge of the site, was the most active. He left his den a few times for brief forays, roamed about and seemed to be keeping an eye on things. Then (just as my air began to run down..) he left his den again and made his way straight to the eastern area where Octopuses 4 and 5 are marked. Two features of the trip were interesting. First, he seemed to know exactly where he was going, and headed straight towards that pair, over a fair bit of open sand. The whole trip covered something like 12 meters. The impression given was that he had a good sense of who was where, at the other edge of the site. As it turned out, he was heading for a male-female pair. On arrival, he evicted the male after a brief wrestle, settled into that male’s den, and attempted to mate with the female.

Second, as he made his way across the sand between those two parts of the site, he went into a “moving rock” mode of travel – see above. This way of moving has been seen in (I think) a fair number of species; it’s not at all rare. But I don’t know if we’ve seen it in this species before, and I’d not recorded it on video. As the tape shows, he produces a rather excellent moving rock, too – highly camouflaged, with arms moving underneath and only occasionally visible..

It’s not clear how his body is organized (he’s moving backwards at this stage), see here for a version of the first photo with the eye marked. These are video screenshots. I will fix up and post the whole video on this website later.

He arrived at the eastern area (see top photo), kicked out Octopus 5, and attempted to mate with Octopus 4.

The moving rock was not surprising; the apparently directed path, straight to the pair he disrupted, was more notable.

Matt Lawrence dropped in on Octlantis again a couple of weeks ago in August, and reports six octopuses, a similar number to February. Matt said that an octopus at the western end of the site was active and curious, standing up, and came out of its den to check him out. I wonder if this was the same one from February?

What of Octopolis itself? Is this the end? Numbers have gone very low and recovered fully in the past. I recorded just two octopuses on the site in 2010, and many more a few years later. Numbers went way down again in 2013, and in 2015 they were high [* I will go into my records and put some numbers in here soon]. Sharks (wobbegongs) sometimes take up residence at the site, as they did in 2013, and this seems to disrupt octopus behavior and reduce numbers. Huge stingrays sometimes come in and mess the site up, feeding.

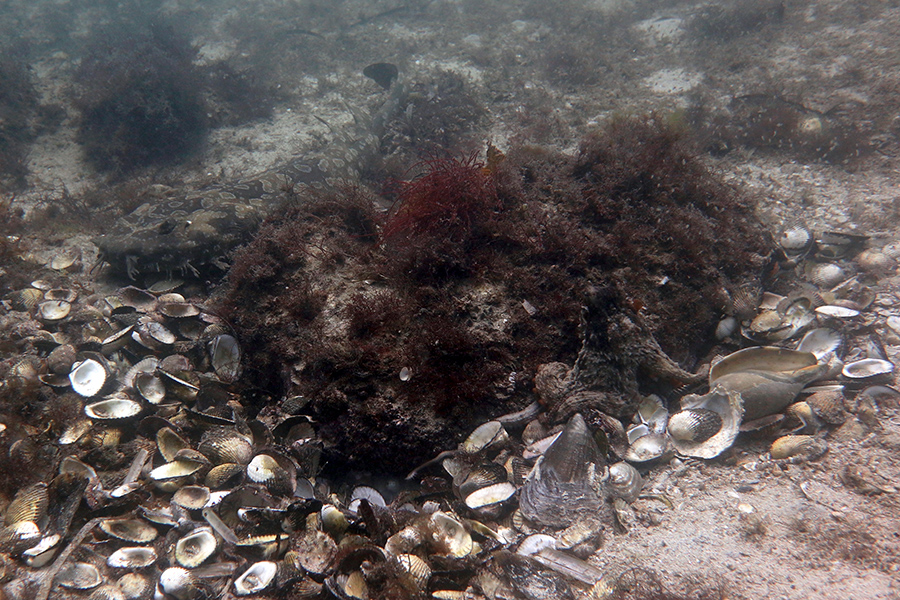

During our February dive, a small wobbegong was lying on the northeast edge of the site, as shown above in the map and in the photo below. Sharks of this species can grow much bigger than this (as discussed here).

Perhaps Octopolis will return to its former levels of activity, perhaps not. The six or so seen recently at Octlantis is a long way from the 13 recorded in 2016, too. Other sites are probably out there, somewhere. Perhaps we’ll have to go searching.

———————-

While I was diving in the Solomon Islands recently, I read Ray Nayler‘s sci-fi novel The Mountain in the Sea. This book, which I enjoyed very much, is about human contact with a highly intelligent and symbol-using population of octopuses in the near future. Octopolis and Octlantis are both mentioned a few times, contrasted with the community in the novel, and are described accurately, without exaggeration. The “Nosferatu” pose also figures in the plot.

The book also deftly handles some dystopian scenarios involving AI and the future of fishing.

I learned today that a play opening shortly in London is called “Octopolis.” A Jervis Bay brewer has released a beer with the same name.  Our group has nothing to do with the play or the beer.

Our group has nothing to do with the play or the beer.

In 2018, Rabbit Rabbit Radio released a song called “Octopolis” (featuring Kristin Slipp) and performed it at Prototype Festival in New York City. Carla Kihlstedt did make contact, and I was able to go to their show, which was excellent.

In 2018, Rabbit Rabbit Radio released a song called “Octopolis” (featuring Kristin Slipp) and performed it at Prototype Festival in New York City. Carla Kihlstedt did make contact, and I was able to go to their show, which was excellent.

The singer takes the point of view of an octopus, comparing their body to the more limited human frame.

“I am all tongue, all taste,

I am receptors, reflectors.

I am layers of light.”

________________

Thanks for the update Peter