The “Pipeline” dive site in Nelson Bay, Australia, has been central to the underwater dimension of my life for nearly a decade (my first dive there seems to have been in August 2013). The site has recently been battered, however, by two years of hostile weather and other problems. I’d not tried to dive there since December 2020 until, a few weeks ago, with some tredidation about what I’d see, I walked down the steps (the steps that open the book Metazoa) once again.

The site is much reduced, no question. It used to be a hidden kingdom in an unlikely place (just off from a fishing coop and a breakwater). Two years of floods – two years of muddy river water coming down on the site from inland – have messed the place up. What remains is more a garden than a kingdom. As I hoped, it’s still good for octopuses. I followed an octopus who embarked on a foraging trip for much of the first dive. Foraging octopuses clamber around, enveloping sponges and bits of reef, probing with all arms.

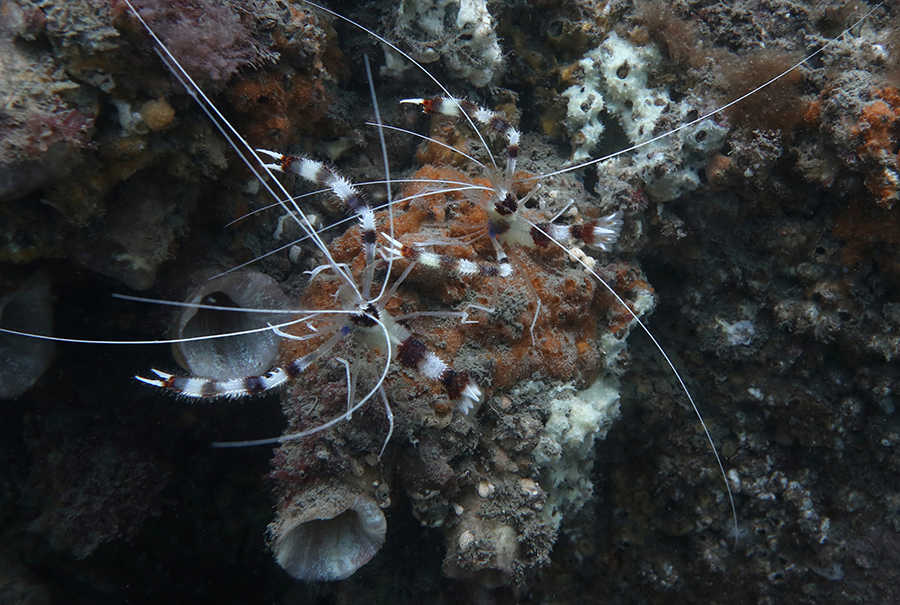

This photo is a bit unusual as the octopus seems to have caught a decorator crab, a crab covered with a personal garden of sponge, other animals (often hydroids), and weed…

.. though the octopus might not have registered the crab at all, if it was staying still.

On the second day, I went back to the same spot, which had about three octopuses not far from each other (maybe 4 meters – definitely separate). I hoped to hitch up with an octopus again on a foraging trip, but missed one setting out and never found him. However, I found an interesting spot in relation to a theme I’ve written about a few times: the commensal tendency in marine animal life. Commensalism refers to animals being willing to share space, to “share a table.” At the spot I found, two green moray eels were poking their heads out over the lower part of the body of a sleeping (or certainly resting) shark, under a ledge. Two very active banded shrimp were poking around on the reef just above.

You can see the shark on the right. These shrimp are the species that feature in Chapter 4 of Metazoa, “The One-Armed Shrimp.” The location was more or less the same as that episode, too.

The morays seemed to be craning towards the shrimp, looking as if they perhaps wanted to be cleaned. I never saw any cleaning, but I think that may have been partly because the shrimp were interested in me, especially in my initial arrival. These two came right out on top of the reef, and one of them (the nearer one, I think, in the first photo) was the most curious and audacious – the most friendly? – that I’ve ever seen, and that comparison includes the original one-armed shrimp from the book. One came out on a little raised vantage point where he was as close to me as he could be, in those circumstances. The other, a bit smaller, wasn’t far away, just back and often a little underneath.

I reached out slowly with with my gloved hand after a while, and the bigger shrimp was very interested in it, sending out those long antennae. A lengthy finger-stroking exchange followed. After a while, I took the took the glove off. I am always interested in whether they much note the difference. In this case, he didn’t seem markedly more interested in me without glove than with glove – maybe a little.

Banded shrimp are difficult animals to photograph, for reasons that relate to their great charm. Those antennae are continually moving (so you need a fast shutter), but they take up a lot of space along the dimension between you and them, with all those limbs and appendages (so you need a small aperture). And they don’t like lights, so ISO is also an issue. I use no artificial light or only a touch (none in these photos). You just have to take a lot of shots and cross your fingers, hoping for a relatively still moment.

I spent about 40 minutes there, leaving once or twice and coming back, until the end of the dive. The eels looked at me if they thought I was distracting their shrimp. The shark slept or rested the whole time.

______

I love the phrase “ the underwater dimension to my life “

Resonates for me PGS although above water is more accurate – your relationship with sea life is always therapeutic to read

Thank you, John.

Down there things move at a slower pace.