Occasionally on this website I’ve criticized the way commentators and activists talk about climate change in relation to other environmental issues – the other issues are too often sidelined. I’ve also been dissatisfied with discussion of how to handle climate change itself. A little while ago, I heard on the radio some ideas that have me organizing my thinking on this issue much more than before. The radio interview was with Jonathan Symons, who works at Macquarie University in Australia (interviewed on Late Night Live, also in Australia).

Occasionally on this website I’ve criticized the way commentators and activists talk about climate change in relation to other environmental issues – the other issues are too often sidelined. I’ve also been dissatisfied with discussion of how to handle climate change itself. A little while ago, I heard on the radio some ideas that have me organizing my thinking on this issue much more than before. The radio interview was with Jonathan Symons, who works at Macquarie University in Australia (interviewed on Late Night Live, also in Australia).

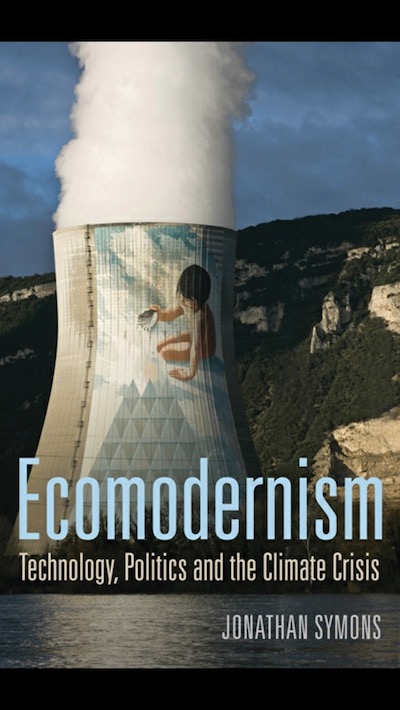

The interview discussed his new book about “Ecomodernism,” a controversial (but not skeptical) response to climate change. Ecomodernists are in favor of technological innovation supported by the state, high-density living, and most controversially of all, nuclear power. I just finished reading Symons’ book – Ecomodernism: Technology, Politics and the Climate Crisis (2019, Polity). It’s an excellent book. The book is about ecomodernism, and is not an unqualified defence of it. Symons himself might be said to be a partial ecomodernist, endorsing some aspects of the movement and criticizing others. I, too, find myself now a partial ecomodernist, but my departures are different from those of Symons.

I will probably write a fair bit about this in various places, now that I’ve started to work out what I think. Here I’ll begin a sketch of my views, contrasting them both to ecomodernism, unvarnished, and to Symons’ variant of the view.

First, what about the photo? It’s a Flamboyant Cuttlefish, Metasepia pfefferi. As far as I know, it has no connection at all to ecomodernism, but this is one of the animals I hoped to see, and eventually saw, in Lembeh Strait, Indonesia earlier this year. These are flamboyant animals even by cuttlefish standards. This one was pretty small, perhaps 3 centimeters long or so, though they can get a little bigger (about twice that size). They are probably toxic to some extent, though it’s not clear yet whether they are dangerous in the way that blue-ringed octopuses are dangerous. (Perhaps this gives them some relationship to ecomodernism.)

Ecomodernists claim that solving the climate problem is largely a matter of technological innovation. This seems right. Specifically, it appears that what is most needed is a new high-density energy storage medium – a synthetic fuel, or something more like a battery – generated by means of renewable energy sources. We may need several of these; we need at least something to serve in power stations that produce “dispatchable” electric power (independent of sun and wind conditions), and something to serve as a jet fuel.

Some commentators (including Al Gore) say that we already have all the technologies we need to solve the climate problem. How does this square with what I say above? We presently have all the needed technologies if people in wealthy countries are prepared to live entirely differently from how they do now, and if people in rapidly developing countries are prepared to forego ever living in this way. Neither prospect seems likely. The idea that it is only “politics” that prevents immediate wholesale adoption of renewable energy also seems unlikely when the same reluctance is seen across vastly different political systems.

I am moderately optimistic about the climate change problem, though, because I am optimistic about our prospects for inventing and deploying the necessary technologies. I say this not because I have special expertise in chemistry or physics, but because of a sense of what is likely given the history of science, and also for another reason. The solution could, in a sense, be quite an inefficient one. It could be inefficient because the energy source used to create the needed fuel will probably be solar and wind, and those resources might be diffuse, but are essentially unlimited. There is no need to worry about getting a lot of the storage medium per unit of sun or wind, as long as we get a lot of the storage medium itself at reasonable cost.

This connects to a second major point. A theme emphasized by Symons, and also (a little less) by the ecomodernists themselves, is the need for large scale state support of this technological project. Nation-states are the only entities that are large enough and able to act on the relevant time-scale; they can invest large sums of money in pursuit of medium-term and long-term gains, including non-monetary gains. If anything, on this point I out-modernize the ecomodernists, and perhaps also Symons. To me it seems clear that the investment in new energy storage media should be truly massive.

The obvious comparisons are to the Apollo and Manhattan projects undertaken by the US in the last century, especially to Apollo. According to a report to US Congress from 2009, these projects, in their peak years, absorbed about 0.4% of US GDP. (That was, at peak, 1% of Federal outlay for the Manhattan and 2.2% for the Apollo – sources and quotes are below.) In 2018 dollars, that 0.4% of US GDP would be about 76 billion dollars per year. That sounds like a size that makes things politically difficult, but I think it is not so difficult – or at least, not compared to every other option. My reasons for saying this take me to point 3.

I used US figures above, but I don’t see this as a project that the US would dominate or direct in any sense. The figures were used to illustrate scale, and the US is one country of many. Does that mean I envisage a huge international enterprise directed at this problem, perhaps coordinated by the UN? No, and this marks my biggest disagreement with Symons.

The last part of Symons’ book is about the role of international coordination, and an ambitious ideal that he refers to as “global social democracy.” Symons sees this ideal as something that differentiates him from other ecomodernists. He gives much emphasis to global justice, and efforts towards trans-national democratic decision-making. Symons and I may disagree about the enduring value of the nation-state in principle, but the point I have in mind here is more practical. I think the way out of our current problem is one with a limited role for international cooperation, not because I am against it, but because I have little faith in it, in present circumstances, and I also see it as unnecessary.

The technological advance I envisage above can align the interests of very different countries. We need it to be economically sensible for countries like India and China to switch to the new approach – renewable sources plus new forms of storage – without having to be cajoled and lectured to by other countries.

The most rapidly growing economies in the developing world are now responsible for a large and rising amount of total carbon emissions. China is first of all countries in total emissions, with the US second and India third. Rich countries still play an outsized role, but countries getting rich are playing an ever-larger one. Western societies’ Green movements, as Symons describes, are generally committed to a future of low-impact, locally based, simpler forms of living. That is how they think the problem must be handled. I doubt that this is politically achievable even in countries where Green ideologies get the most traction, places where progressives can wistfully envision moving beyond a life of high-impact bustle. It surely has even less chance in countries with newly expanding middle classes who are just starting to live in high-impact, luxurious ways.

The optimistic picture I have in mind is one where massive state investment by some country leads to the required technology, and it rapidly becomes rational for others to use it as well. There’s no reason why the country making the breakthrough should be the US, and present conditions in the US make it seem somewhat unlikely. But those earlier US projects show how the rather special kind of accounting in play can work. Part of the accounting involves national prestige, something that is irrelevant to the private sector but politically powerful in democracies. Whether or not Apollo itself was worthwhile, it shows what is politically possible at this scale.

Above is the cover of Symons’ book. When he was interviewed on the radio show where I first came across these ideas, the interviewer (Philip Adams) often had a tone of deep disageement with his guest. This, as far as I could tell, was entirely due to the most controversial part of ecomodernism, one that tends to overshadow everything else: advocacy of nuclear power.

I depart from ecomodernism on this point as well. Whether or not it would be sensible in principle, it seems fruitless to pursue large-scale expansion of nuclear power as part of the solution. The political opposition to it is so intense, and so likely to cause polarization and breakdown of discussion, that I would take it off the table for those practical reasons. Nuclear power has exactly the same downside as elaborate international cooperation: it is not feasible in the medium term. Just as “global social democracy” is unhelpfully utopian, nuclear power is unhelpfully polarizing. (Here I refer to fission reactors, not fusion technology, which may one day come good.)

Ecomodernists seem sometimes to relish the controversy around their advocacy of nuclear energy (here I do not include Symons). This seems to be related to a more general image problem. Reading work coming out of the movement, I often find myself forming a mental image of energetic slender men in Star Trek jumpsuits. I think the ideas around ecomodernism would be gaining more traction if they did not come with this image in tow, and the tone of their advocacy of nuclear power is part of that problem.

Temperamentally and aesthetically, I quite like the more familiar Green image of a simpler, lower-tech life. But climate change has become a problem for the short and medium term. It’s nonsense to talk as if the “world will end in 2030,” as some do, but this is no longer an issue to kick down the road. The form of ecomodernism I am starting to sketch here (and will continue to fill in) is designed to be practical in the short and medium term. These are ideas that can be naturally used and made vivid by centrist political parties – parties in worldwide retreat right now. These ideas give centrist progressivism a message other than the politically doomed one of self-denial and restraint. In addition to this practical side, there’s a background element in the ecomodernist worldview that I do endorse, in contrast to much mainstream Green thinking. Humans are transforming the Earth now, and before us, life of different kinds was transforming the planet for countless millennia. Attempting to opt out of the project of active transformation of the planet as far as possible is coherent, I agree, but that mindset should not enjoy any allure of “naturalness.” It makes more sense to accept that we will be directing a lot of change on the Earth, and attempt to do it well.

I have used up my Metasepia photos, but it is good to finish with a picture. Yesterday my octopus collaborator David Scheel sent me an email with the photo below. He’d seen my previous post on the mysterious Melibe. David took this photo in Alaska. In the middle is a wonderful Aeolid nudibranch, Hermissenda crassicornis, and around it are many individuals of Melibe leonina, the lion’s mane Melibe – “with hoods extended, suspension feeding in the water column. They cling to the tops of eel grass when doing this. These lion’s mane nudis are very common some years in Prince William Sound.”

___________________

Notes

1. The most prominent organization associated with ecomodernism is the Breakthrough Institute. Their “ecomodernist manifesto” is here. One of the most vocal figures associated with the movement right now is Michael Shellenberger. He co-founded Breakthrough with Ted Nordhaus but seems to work mostly now with a different group, founded by him. Shellenberger wrote a good recent essay in Forbes about the relation between climate change and other environmental problems. Judging from his twitter feed, he is among the most relentless advocates of nuclear energy, and positively hostile to Green groups that oppose nuclear power. He also speaks out against overly apocalyptic views of the situation. That material is intriguing, though with a drought-fueled early-season bushfire burning 6 miles from where I type this, one of several sending huge clouds of stifling smoke down into children’s lungs in Sydney, I wonder if he overstating this case.

2. A passage from that report to US Congress about high-cost US programs of the 20th century.

In 2008 dollars, the cumulative cost of the Manhattan project over 5 fiscal years was approximately $22 billion; of the Apollo program over 14 fiscal years, approximately $98 billion; of post-oil shock energy R&D efforts over 35 fiscal years, $118 billion. A measure of the nation’s commitments to the programs is their relative shares of the federal outlays during the years of peak funding: for the Manhattan program, the peak year funding was 1% of federal outlays; for the Apollo program, 2.2%; and for energy technology R&D programs, 0.5%. Another measure of the commitment is their relative shares of the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP) during the peak years of funding: for the Manhattan project and the Apollo program, the peak year funding reached 0.4% of GDP, and for the energy technology R&D programs, 0.1%.

Above I mentioned just the Apollo and Manhattan projects; the report also discusses energy-related R&D measures after the “oil shock” of the 1970s. In some ways that is more directly relevant to the present situation, though the project is less well-known and I think the political climate at present makes the Apollo project the most comparable.

3. My figures on the CO2 emissions of different countries come from the Union of Concerned Scientists website.

4. Why do I think that solving the energy storage problem is so pivotal? What about droughts and other problems involving fresh water? What about agricultural impacts on climate? What about inundation of coastal areas due to processes already underway? In the case of water, I do think energy is still central, as sea water plus electricity yields drinking water. Desalination with renewable energy is surely a large part of the way forward. The other issues I’ll discuss another time.

Great to see another philosopher of science take a look at ecomodernism! I became involved in it one and a half years ago and even co-founded an ecomodernist society.

Great blog post, and I sympathize with much of what you write. Jonathan Symons’ book is amazing, he is such a wonderful writer.

I would like to defend the ecomodernists’ focus on nuclear energy. I suggest to think of it this way:

Fossil fuels have extreme advantages: they’re energy-dense, easy to store, to transport, abundant, and there’s infrastructure for their use. Renewables with storage might be able to fully replace them in one central application (electricity), but nowhere in the world (except where hydro-resources are excellent) are we close to realizing this at affordable costs. But it is highly doubtful whether such a system will be competitive, let alone, cheaper than a partly fossil-fuel powered system in the next decades.

Extremely cheap storage, together with further falling costs of wind and solar and extremely cheap transmission, could change this, but it is very risky to put all our eggs in this basket. Certainly, very cheap abundant long-term storage will not be there in the short term. That does not mean that we should abandon the goal to get it as quickly as possible, but there is really no guarantee that it will be there soon enough to make fossil fuels dispensable, let alone unattractive.

With nuclear, in contrast, there is a lot of historical precedence that it can be built at costs (say, below 3000 US-Dollars per kW) which make (almost) complete decarbonization of electricity quite affordable and potentially even attractive. So we know that it’s physically possible. You are absolutely right to point out that the huge social and cultural resistance against it make it very hard to get (back) to a point where a majority wants it and it becomes economically attractive again, but in my view it’s just as worth trying as is trying to get to very cheap storage.

Can you appreciate the point of this being an opportunity to diversify our risks? Or do you think that the chances of people changing their minds are much lower than the chances of getting to very cheap storage (and further falling costs of renewables and cheap transmission).

And regards nuclear being divisive, I’m not sure about this. Yes, it can drive a wedge between climate-concerned actors, but it might also be used to forge alliances with the traditionally climate-skeptical political right. Difficult to predict how this will balance out in the end.

Thank you for this. Here are some thoughts.

“Can you appreciate the point of this being an opportunity to diversify our risks? Or do you think that the chances of people changing their minds are much lower than the chances of getting to very cheap storage (and further falling costs of renewables and cheap transmission).” I suppose I do think something like that, though of course it is very hard to know. On the nuclear side, the problem of waste storage seems to be one that is very unlikely to go away (just like the waste). I have been reading a bit about the difficulties of getting long-term waste storage facilities accepted in the US and Australia, even in the most geologically suitable places. That situation does not look promising at all.

I wonder also what pro-nuclear people envisage for the countries in the developing world that are responsible for a growing proportion of emissions. It’s all very well to persuade the Germans and other Europeans to head back towards nuclear, but is that a plausible global solution? A renewably produced fuel – something akin to “green hydrogen,” but safer and denser – can be a global solution, in contrast.

With regards to developing world, the situation is quite the opposite to what I think your impression is. The highest resistance to nuclear energy is in the West, developing world is very keen on nuclear energy, and for two very good reasons

1. They see it as an item of prestige and modernity

2. It brings development benefits. Unlike solar panels and wind turbines, that are manufactured elsewhere and then just plopped in, building nuclear power plants are construction projects that also employ local construction industry and bring technology transfer. In addition, to be able to operate and regulate nuclear power plants requires highly skilled workforce. This means that whoever is selling you a power plant will also take on itself a task of taking large number of people from your country and training them as engineers and scientists.

And finally, in developing country, most of the population doesn’t know what “nuclear” is, and doesn’t harbor all misconceptions and prejudices that the developed world has.

I agree that transferrability of technology to developing countries is absolutely key. Some developing countries, e.g. India and Bangladesh, do corrently build new reactors, and many more would doubtless follow if suitable and cheap options were given to them. I don’t know whether you have seen this report by The Breakthrough Institute on the potential for new nuclear in Africa:

https://thebreakthrough.org/articles/atoms-for-africa

So ecomodernists do consider this point.

And in any case I also agree that a low-carbon generated highly dense fuel would be very useful, perhaps a hydrocarbon which could be conveniently deployed with existing infrastructure.

Thoughtful criticism of Ecomodernist’s insistence on the need for civilian nuclear power.

I’ll take the liberty to respond frankly.

I was a bit taken back by the link to the UCS website, since the UCS is an antinuclear (and antiGMO) propaganda group, and I would not recommend relying on them for information about nuclear or biotechnology. Yet, your noted concern about nuclear waste indicates that relying on the UCS is just what you have been doing, since the UCS’s (and other antinuclear groups) primary tactic has always been to exaggerate the risks while obscuring the opportunities of nuclear waste management. It’s a strategy known as “constipating the fuel cycle” and there are many who fall for it.

A far more objective and constructive review of the nuclear waste question has been compiled by the American Physical Society, and I would certainly recommend reading that next to the UCS perspective.

A key part of the Q&A for policymakers imbedded in the APS review states:

Q1. Should there be a moratorium placed on the construction and licensing of new reactors in view of uncertainties about how to dispose of nuclear waste?

A1 We see no need for such a moratorium. We are confident that

long-term isolation could be effective for either spent fuel or the

high-level and transuranic waste, and that there are no important

technical barriers to the development of a repository on a pilot plant

scale by 1985. The corresponding regulatory and licensing basis is not

yet available, but we see no reason why it cannot be completed in an

orderly way

“Report to the American Physical Society by the study group on nuclear fuel cycles and waste management” – APS 1978

https://journals.aps.org/rmp/pdf/10.1103/RevModPhys.50.S1

The take away is that nuclear waste has never been a technical, economic or environmental problem, but only a political one, nurtured and wielded deliberately as such by groups like the UCS to pursue their antinuclear agenda.

That said, I agree with you that nuclear in its broad complexity, history and gravity is a difficult subject, and hence that if the technology isn’t strictly needed for addressing the climate/energy nexus, then it’s probably better to just ignore it entirely.

However, as an engineer consulting on energy issues for almost 20 years now, I’m confident that nuclear *is* strictly needed, and I’m not the only one.

Quotes IEA:

Achieving the pace of CO2 emissions reductions in line with the

Paris Agreement is already a huge challenge, as shown in the

Sustainable Development Scenario. It requires large increases in

efficiency and renewables investment, as well as an increase in

nuclear power. This report identifies the even greater challenges

of attempting to follow this path with much less nuclear power.

It recommends several possible government actions that aim to

ensure existing nuclear power plants can operate as long as they

are safe, support new nuclear construction and encourage new

nuclear technologies to be developed.

“Nuclear Power in a Clean Energy System – IEA 2019”

https://www.iea.org/reports/nuclear-power-in-a-clean-energy-system

Moreover, I submit that *all* energy experts who deny or ignore a significant role for civilian nuclear in addressing global warming do so not because they honestly believe nuclear is not required, but vainly because they seek to avoid precisely the difficulty noted in your article. They do it for personal reasons having to do with protecting their positions and reputations. As someone who could not stomach the thought of having to join the antinuclear lobby in order to “get ahead”, I have experienced that they are right to fear the power and influence or antinuclearism, and hence I can understand their cowardice.

In my view though, an Ecomodernism that opposes or ignores nuclear energy for tactical reasons is no better than the existing antinuclear “green” establishment, and has little or nothing to add to it. It might as well not exist.

Rather: I believe that the obvious difficulty of overcoming antinuclearism should – if anything – be advertised by ecomodernists as a sign of our seriousness (and factfullness) in dealing with the climate/energy challenge.

By stressing the importance of nuclear, ecomodernists also help dispel the “climate skeptics” argument that “if climate change is really a problem, why are the Greens opposed to nuclear energy?”

I end by remarking that your image of the ecomodernists in Star Trek jump suits stuck me as odd, because that is the picture I have of the antinuclear greens, who never stop insisting (for 40 years and counting) that “green” technology will solve climate/energy without the need for nuclear.

My own image of ecomodernists is rather more plain: simply normal people who want to fix the things we can fix with the science, knowledge and tools and assets that we have at hand, right now. No procrastination. No nonsense. No reliance on ” silver bullit” solutions that don’t even exist in theory. No reliance on people withdrawing voluntarily – globally – from material “creature comforts”. But reliance on confidence and trust drawn from proven principles of science, industry, trade, negotiation, compromise and cooperation. That’s all humanity has ever had, and has ever needed, and it will be enough.

Some replies here:

1. “I was a bit taken back by the link to the UCS website, since the UCS is an antinuclear (and antiGMO) propaganda group, and I would not recommend relying on them for information about nuclear or biotechnology.” I only used UCS for the figures about carbon emissions due to different countries – their graphic is a good one, with the right amount of detail. I did assume that though they are an advocacy group, they’d be reliable for basic factual material. I don’t rely on them for other claims about nuclear power. Their carbon figures come from this organization: https://www.iea.org. For the top four countries (China, USA, India, Russia), their 2019 figures are very close to the 2018 figures on Wikipedia, that are claimed to come from the EU. (A difference is that the UCS 2019 figure for USA is 16% and on Wikipedia for 2018 it is about 14%).

“Yet, your noted concern about nuclear waste indicates that relying on the UCS is just what you have been doing….” Not at all. I’ve not read anything from UCS about waste. You might be more careful in making claims about who has been using what sources.

2. You say: “The take away is that nuclear waste has never been a technical, economic or environmental problem, but only a political one….” In my post I say: “Whether or not it would be sensible in principle, it seems fruitless to pursue large-scale expansion of nuclear power as part of the solution….” I am agnostic about whether it would be sensible in principle, given the technical tasks and challenges. I think the political side is the big problem. I say: “The political opposition to it is so intense, and so likely to cause polarization and breakdown of discussion, that I would take it off the table for those practical reasons.”

3. You say: “Moreover, I submit that *all* energy experts who deny or ignore a significant role for civilian nuclear in addressing global warming do so not because they honestly believe nuclear is not required, …. They do it for personal reasons having to do with protecting their positions and reputations.” This seems to be another very confident interpretation of others.

Thanks for your reply, I stand partly corrected.

You maintain (as the UCS would have us believe as well) that nuclear waste is a technical challenge whereas it has long been identified as a purely political one by the APS and other scientific institutions.

My assertion that all energy experts agree that nuclear energy is beneficial, necessary and sufficient for solving the climate/energy challenge is based on nearly two decades of joining the energy debate.

Experts who appear to oppose nuclear energy do because they are not experts (f.e. they think nuclear is not low carbon, uranium is scarce, power causes bombmaking, waste is unsolved, or nuclear is costly, slow or constrained) or because they are crazy (civilisation will collapse sooner or later and all nuclear technology must be eliminated before that happens) or because they are evil (nuclear frustrates the interests of my paymaster).