Day 3 of the Fly Point dive trip. Another post to frame some photos of octopuses in shallow water.

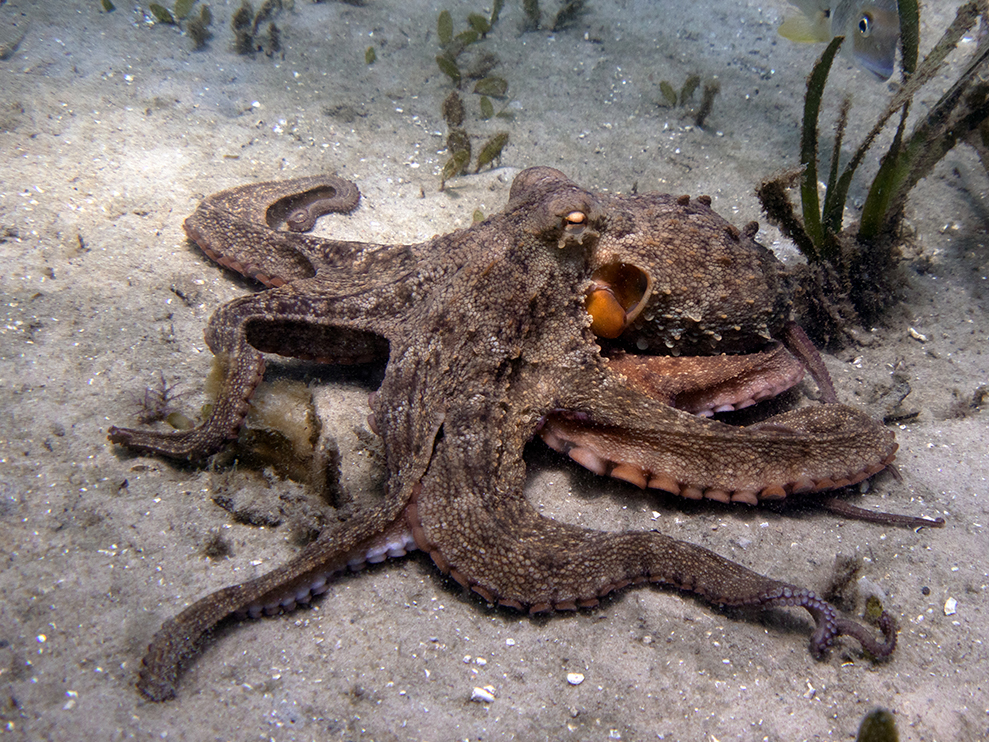

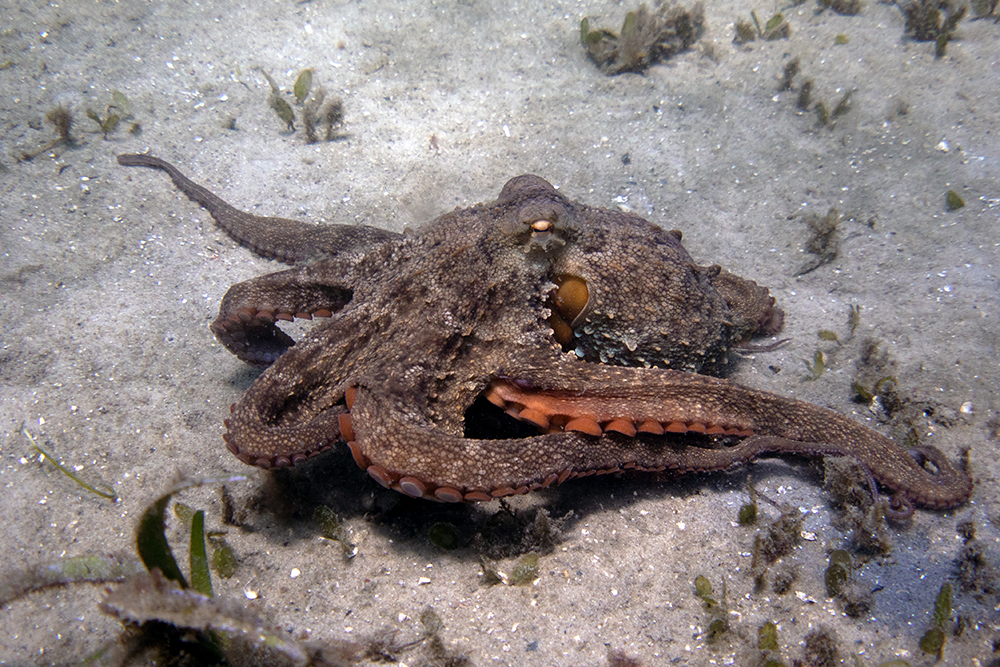

Heading into the shallows, in a flat seagrassy area, I saw a bit of old pipe that looked like a good octopus den. A big octopus was curled up inside, in a position I associate with females brooding their eggs. Then I realized there was another very large octopus parked right in front, in some weed, very close to me. I am pretty sure this was a male (especially from the large suckers on the upper part of his arms). He was one of the biggest octopuses I’ve seen for a long time. He was in great condition, sitting there watching me, and – I assume – guarding her.

She, too, had good-sized suckers – it would not be clear from the suckers that she was female; I am going on the fact that she was curled up inside and he was parked outside and pretty clearly male.

I had plenty of air and time, so after scouting and taking a few pictures I floated at the surface and watched.

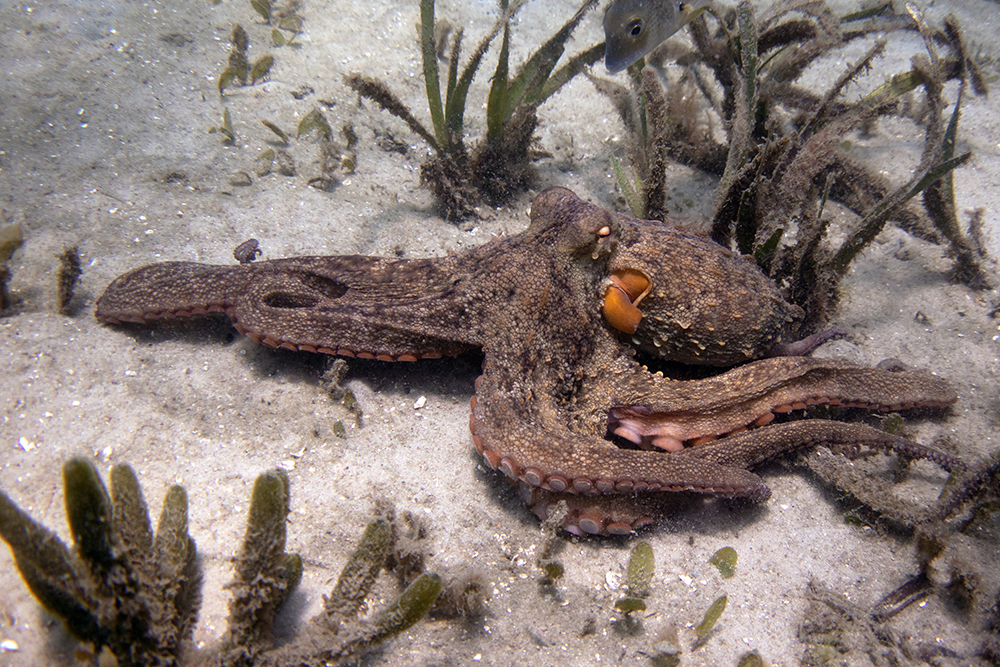

After a while he set off, and did a long foraging trip that I followed for about 45 minutes. He hunted in the usual sort of way, and did a pretty clear circuit round the pipe and the other octopus. The radius was something like 3-5 meters. I would go up occasionally as I couldn’t see the pipe from down alongside him, but he seemed to maintain that radius without much difficulty, and went, I think, all the way round.

He had two encounters with other animals. At one point he was in a bit of weed and there was a jolt and aggressive movement, and a small dark eel raced out and sat nearby on the sand looking startled. It wasn’t a tiny eel – perhaps a foot long – but the octopus definitely had the upper hand. The eel left. A little later he went into another bit of weed and there was another startle, and this time he jumped back, very rapidly. I couldn’t see what it was – suspected it was a buried numbray, perhaps (an electric fish), mainly because there was no sign of a toothy animal that might have bitten him.

By this point I was low on air. He reached a rock with what looked like another octopus den, perhaps a den he’d used himself, about 2 meters from the pipe and with a decent view of it. He cleared a bit of rubbish from the den but didn’t settle inside, and instead climbed up and sat on top of it. I thought: this is a den from which he can watch the other spot. I expected him to settle in, so I went up to the surface and hovered, but rather than settling he moved off, and now also away from the pipe. My tank was almost empty and it was time to go. I waved goodbye and headed in.

Perhaps because of his size, as I watched this octopus I felt more able to imagine being inside – being – that body, with all the arms and the endless flexibility. Perhaps it was also his vigor, which was considerable. I was more able than usual to imaginatively project myself in there.

_______________

Notes:

If you write a comment on the post from this front page, the letters will look very small as you type. Write from here to avoid the problem.