In Chapter 1 of the book Consciousness and the Brain, Stanislas Dehaene runs quickly through the history of his topic. Early on he discusses research done about 20 years ago on “binocular rivalry,” by Nikos Logothetis and his coworkers. He says something very strong about that work: “This was, literally, the first glimpse of a neuronal correlate of conscious experience.”

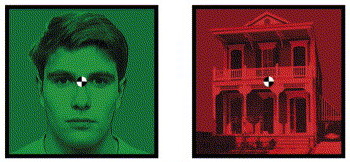

What was the glimpse? The experiments were very clever. It had been known since the 19th century that if entirely different images are shown to each of a person’s eyes, their conscious experience does not fuse the two, but flips between them. If one eye is shown nothing but a face and another is shown a house, your experience will be house.. then face.. then house….

In a series of experiments Logothetis did with various collaborators (David Leopold, Jeffrey Schall), monkeys were first trained to use a lever to indicate which image they were seeing in a rivalry situation (working out how to do this was itself a tricky task – how do you know the monkey is not just pulling the lever at random? After all, the stimulus shown to the eyes is not changing). The researchers then recorded the activity of neurons at different places in the monkey’s brain, to work out which neurons were active when one image, or the other, was being experienced. They found, among other things, that at the “early” stages in visual processing, the activity of neurons mostly reflected what was being presented to the eyes, but deeper in the brain, there were many neurons whose firing was associated with the monkey’s report (with the lever) of what it experienced. Just as Dehaene says, it was “the first glimpse of a neuronal correlate of conscious experience.”

Since then, binocular rivalry has been a fertile area for research into consciousness. This post is mostly about another kind of rivalry, though.

The lab where Logothetis currently works is in Tübingen, Germany. I was in the area, visiting a different lab, late last year, and saw that several labs had hired extra security. Shortly before I arrived, some undercover footage had been released on German TV, taken at the Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics, which includes Logothetis’s lab. The footage showed what appears to be terrible suffering of monkeys used in that institute’s research. The video is on YouTube, here. I don’t want to embed it on this page, as the images are too awful.

The first thing to say is that I have no knowledge of whether these monkeys are used in Logothetis’s own work. They might be, and they might not. This work might be entirely separate from his, for all I know. There are about seven separate labs in the institute. Logothetis, who is the institute’s overall director, did write several of the lab’s defences of its monkey work (here and here) after the footage came out, but this does not imply that these particular monkeys were his responsibility.

The reason I am focusing on the Logothetis research in thinking about this issue is the fact that, on one side, I see this as very valuable scientific work. As Dehaene says, this research program takes us quite far into an extraordinarily difficult problem, the problem of the neural basis of conscious experience. We have learned a lot from what he did. But whenever you read a report of a neuroscientific study based on “single-unit recording,” or measures of activity at a single neuron, the monkeys have been implanted with machinery in their brains, of the general kind seen in the video; that is how the recordings are done. I’m prepared to believe that in most cases there is nothing like the trauma evident in the video from the Biological Cybernetics Institute – that something went badly wrong in that case. But even when things go “well,” the stress and other suffering inflicted must be very great. Should this kind of work be done at all, even when it leads to findings as valuable as Logothetis’s?

That’s the problem, one of rivalry between two goals – the goal of learning about the world, and the goal of not causing suffering in complex and intelligent animals whose lives we control.

I had some conversations about this with scientists in Tübingen, though I didn’t meet anyone from the cybernetics labs. In those conversations I heard two things. First, people were furious with animal rights activists for what had happened after the video came out. Some of the staff at the institute, including administrative people with no role at all in the treatment of animals, had received death threats, and were under enormous stress. This was a very bad mistake by the activists (I don’t claim that the groups who made the video had any involvement in the threats). The threats had the consequence that every scrap of available sympathy in onlookers was directed at the humans, not the animals. Most conversations I tried to have about the monkeys just came back to the death threats. They could not have been more self-defeating.

The other thing people talked about was the benefits that have come from monkey work of this kind – scientific and medical benefits. The cybernetics institute is concerned with “basic” research, not medical research, but I’m entirely prepared to accept that medical benefits will accrue from this work. An example cited several times was the way that “invasive” techniques using implants and surgery through the skull have been used to calibrate and improve non-invasive techniques for studying the brain, such as fMRI. Logothetis himself is responsible for some of this work. Animal activists sometimes argue that the benefits from cruel work on animals are illusory, or could more quickly be gained in other ways. I am doubtful of that, so for me, the rivalry is real.

How is the rivalry to be handled? Here are some suggestions that I think can be defended.

1. I would phase out invasive research on monkeys that is driven by scientific curiosity. All those qualifiers are important – invasive, monkeys, scientific curiosity. In the case of research that has a definite medical goal, it’s possible to at least attempt a calculation: is the amount of suffering that will be caused outweighed by the amount that is likely to be prevented? That is a hard question to answer in most cases, but it’s possible to try, and once we try, we’re in a much better place than before. Work driven by scientific curiosity I put in a different category, even though the line between the two is not sharp.

2. The view defended above is far from saying “end all research on animals.” I am not an expert in this area, but my understanding is that monkeys are not used a lot in basic research now, especially outside neuroscience. A huge amount of work is done with other organisms, especially mice, fruit flies, nematodes (tiny worms), and a small fish called a zebrafish. Of these, mice are the obvious cases to think about next. In the case of laboratory mice I would apply a similar line of reasoning to the one I apply to farm animals. It’s not too hard, for animals like cows and chickens, for us to make a distinction between a life worth living and a life not worth living. Factory-farmed animals, especially pigs and battery hens, lead lives so bad the animals would be better off having never lived at all. (Suppose reincarnation was real: would you prefer to come back as a battery hen, or not at all? On the other hand, would you rather come back as a free-range chicken roaming around one of the best organic farms, or not at all? The thought-experiment can’t be taken too seriously, but for me, both questions have pretty clear answers.) In the case of laboratory mice, at the very least we can do this: give them a longer and better life, overall, than their wild cousins. That would be a start. Once we were doing that, the debate about further restricting mouse work, or not restricting it, is a debate in the realm of reasonable options.

One of the ironies in the case of Logethetis is that his work taught us about important similarities between subjective experience in humans and monkeys. I’d expect that these findings will, as they filter around, lead to more consideration being given to the experience of animals. The finding makes me more inclined to oppose a continuation of that very work. To call for an end to invasive work on monkey brains is to accept that findings of this kind will come more slowly. A person might then say: “Would you have put an end to this work at an earlier stage, before we knew how the visual cortex works, before we’d made fMRI, which is so useful and humane a method, into something reliable? Would you have shut us off from all those gains? If not then, why now?” I would not have minded if the results had come more slowly. After all, lots of scientific and medical results would come quicker if we used humans, not animals, in the research. We’re willing to live with those delays; I could live with others.

UPDATE, May 2015: Logothetis has announced he is abandoning his work on primates, and from now on will work on rodents.

* * *

Notes [to the original post]: Here is the web page put up about the Max Planck lab by the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection (BUAV), with their full account. The other organization involved in the investigation was Soko-Tierschutz.

The Huffington Post has been one of the few US media organizations to take a close interest in the case, publishing pieces on both sides (see here and here). The New York Times just published some reflections by an ex-experimenter.

While on the topic of animal welfare, the Australian abomination in this area, the live export of animals packed on crowded ships to middle-eastern and asian countries where they are killed with great cruelty, continues unabated. The latest information about it is here.

For nudibranch people: Goniobranchus albonares.

Time. Perhaps the most significant word in your thoughts when considering if, when and how to use animals in testing. You may not be quite old enough to remember polio where I have known people that survived it (by happenstance, here is a recent article – http://phenomena.nationalgeographic.com/2015/04/12/polio-60th/). The heavy use of unproven herbal remedies, for better or worse, also points to time in that we have not yet found ways to alleviate many common aging problems but we are suffering with them NOW and will not be around when (and if) proven solutions are found. I am also the beneficiary of having multiple family members around much longer than would have been possible a generation ago. I delight in seeing our technology approaching reducing/eliminating the need for using live animals (http://wyss.harvard.edu/viewpage/461/) but understand that, in MY lifetime many of the life extending/life quality treatments have been dependent on cruelty I would rather not think about but have to accept as essential to the outcome. It appears we ARE moving away from animal testing in non-essential areas (cosmetics) and looking for alternatives where the outcome in less sophisticated biologics does not produce the same results in humans and few would not applaud this advancement for both outcome and cruelty concerns but for many of us TIME is not on our side.

Hi Denise,

The post does not oppose animal testing in medical research. It opposes “invasive research on monkeys that is driven by scientific curiosity.” I accept that there is not a sharp line between this sort of work and medical research, but even a vague boundary can be an important one.

Your comment made me curious about the case of polio. This is a case that both proponents and opponents of animal research like to cite. It seems the crucial large-scale testing in this case was done on humans, not monkeys. I assume it would be very hard to do that testing now. There was some monkey work that led up to the human trials. How important was the monkey work? The opponents of animal testing quote a comment made by Albert Sabin, years later: “… prevention was long delayed by the erroneous conception of the nature of the human disease based on misleading experimental models of the disease in monkeys.” I need to have a closer look at this quote. In any case, Rivalry does not oppose all use of animals, even monkeys, in medical research. I do think the use of monkeys and apes in this work should be very rare, and restricted to cases where the balance of harms and benefits is unusually clear.

My first thought on the polio commentary is, “Hindsight is 20/20”. Would Sabin agree that we should have started experiments on humans and that fewer humans would have been negatively impacted? Would we even have a vaccine (especially today)? He had the benefit of failures to try a new approach and to reinvestigate ignored findings (that were likely ignored for a reason – albeit the wrong one)…. [Denise’s full comment is here – PGS]