The gorgons in Greek mythology were three snake-haired sisters – Medusa the most famous – who were daughters of Echidna and Typhon. (Australian Echidnas may have been named, by Cuvier, for Echidna, referring to their chimeric appearence.)

Under water, gorgononians are octocorals – soft coral colonies made of many flower-like polyps. At Nelson Bay, Australia, gorgonians are often bright yellow. (The genus is apparently Euplexaura, though I don’t know a lot about them.) They are beautiful in their own right and also a branching nearly-one-dimensional home for various other animals.

A particular range of inhabitants seem to seek them out. These include seahorses,

Cowries, often perched high on a branch. . .

Also feather stars – I don’t have a good photo yet – and tiny crabs and shrimp (this photo is from the same site, by Dave Harasti).

My eye is so often caught by these inhabitants, but the gorgonian strands deserve attention in their own right. Here is a close-up with extra light:

And closer still. Each of those flower-like shapes is an individual coral polyp.

Stepping back again, now further than usual, a crowded gorgonian can become a living counterfactual representation of the genealogical tree, bearing representatives of different groups on each branch. (Might seahorses have been ancestral to all those different kinds of algae?)

_____________

COVID NOTES

The last two posts on this site took a break from Covid and the lockdowns. It’s time for another look. This will be my last foray into politics and current crises on this website; as we edge closer to the publication of my next book (in November), one featuring the animals of this site, I’ll move all the politics somewhere else.

In earlier posts (1, 2, 3), I wanted to make the following points. First, we should frankly confront, not be willfully blind to, tradeoffs between the direct health effects of the virus and the effects on health and wellbeing stemming from the lockdowns imposed in many places. Some people (especially those with lockdown-uninterrupted salaries) seem to see it as callous to think about this situation as a trade-off; I think it is callous not to think of it that way. The suffering caused by economic and educational dislocation is more diverse, diffuse, and less visible, but it often becomes a life-and-death matter, and at some point these losses surpass any gains. It is reasonable to try hard to slow the spread of the virus, using all the technology at our disposal, but there are ways to do this without destroying countless thousands of livelihoods. And the reasonable goal is to slow the spread and prevent health systems from being overrun, not to try for elimination of the virus in the absence of a vaccine. Without a vaccine, even successful local suppression encounters the perennial problem of re-introduction from outside. In those posts I also lamented the sudden disregard for basic liberties – how crude and unintelligent the enforcement of lockdown rules has been in places like Australia and the UK.

A few months on, how do things look? In many places, infection rates are up again, and crackdowns by local authorities have again been alarming. In Australia, we may become victims of earlier temporary successes. Infection rates for a time seemed so low that it appeared feasible to knock the virus out altogether. When infections increased again, that new goal, or something close to it, seemed to have become lodged in people’s thinking. The result has been “Covid mission creep” of a worrying kind.

In the state south of here, Victoria, I’ve seen disregard for liberties of a kind I’d never have countenanced in an elected center-left government. The state government locked down 3000 people, suddenly and without warning, in public housing high-rise towers, where police prevented anyone from leaving for 5 days. These people had broken no laws, and were confined merely because of an elevated Covid rate in the buildings (about 23 cases at the lockdown stage). I can still hardly believe it as I type it.

Finding myself out of line with mainstream views, I have been reading heretics. Earlier, I discussed the economist Gigi Foster‘s analysis of the trade-offs that lockdowns involve. A more detailed column of hers is here. On the epidemiological side, one of the main voices for unorthodoxy has been Michael Levitt, a Stanford biophysicist. Levitt has “NP 2013” – Nobel Prize 2013 – as part of his twitter name (@MLevitt_NP2013), unfortunate perhaps, though the prize no doubt helps his views get an airing. His twitter site has become a clearing-house for unorthodox but scientifically informed thinking about the pandemic.

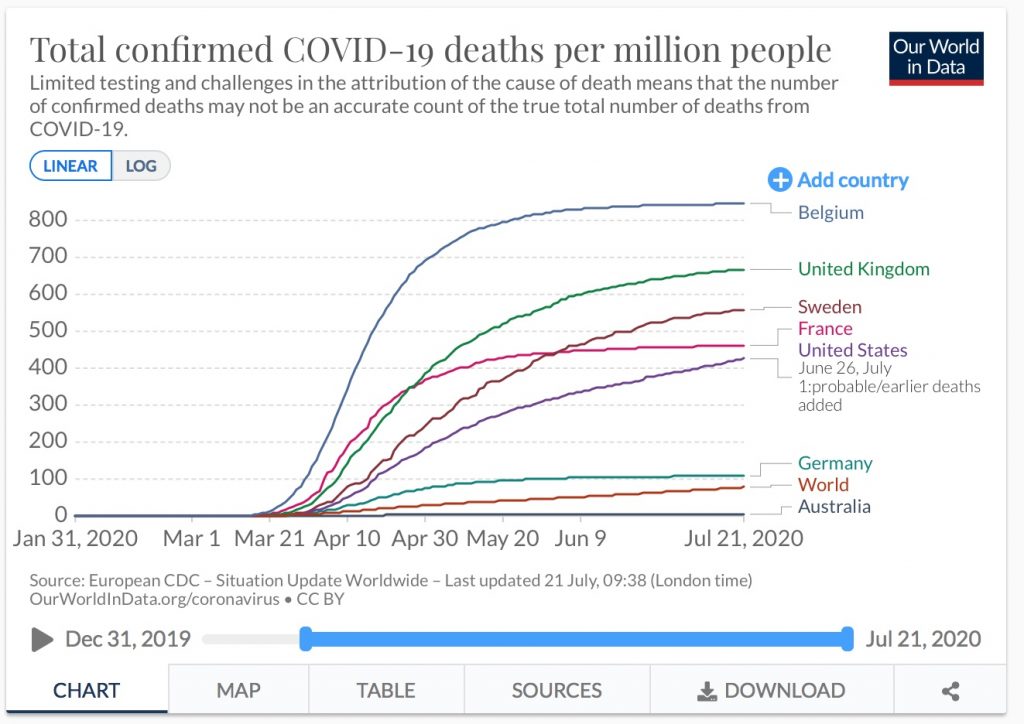

Levitt’s rough initial picture, as I understand it, was as follows. If, though deliberate policy or sheer disorganization, the virus spreads widely in a developed country, then the death rate will reach roughly 500 people per million in population, and then subside. Overall susceptibility to the virus is lower than it first looked, for some reason, and mortality is lower too. The virus starts to run out of victims naturally around that point. Sweden, where life was deliberately allowed to continue roughly as normal, reached a 500 per million figure a while ago, and deaths then slowed (though they have not stopped). A number of other countries have started to flatten around the same 500 per million figure. Some countries successfully prevented this degree of spread of the virus, at vast cost, but (on this view) are now merely waiting for a similar outcome – bad, but not catastrophic – to arise later on. That will happen unless a vaccine is found.*

I say that was Levitt’s “initial” picture – new data has been inconsistent with at least some parts of it. The 500 deaths per million figure has been surpassed by quite a lot in the UK (667), and by much more in Belgium (845) and a few other countries. Factors like age distribution, overall health, behavioral habits, and genetic and immunological quirks in populations apparently have strong effects. In specific parts of some countries (New York City, and Bergamo, Italy) the rates are much higher still.

The bigger question, though, is whether something roughly like this picture is right. A quick look at the data in different countries shows a flattening of death rates in many places, even if the flattening is not heading to the same place.

The chart above comes from this site, where you can focus on any set of countries you choose – I’ve included the ones mentioned above, plus one or two others for comparison.** In many developing countries, the picture is different.

The partial flattening is occurring despite disparate public health approaches being taken. Sweden alone shows that the doomsday scenarios promoted by many epidemiological insiders were badly misleading.

A large-scale and ominous test bearing on the main question above is occurring right now in the US, where the virus is spreading rapidly. Will death rates level off in a similar way there, too, perhaps at 500 per million or at a UK-like level? Or is the US headed to a worse outcome?

Even if it does, the basic points above about trade-offs still hold.‡ And where things are less dire, a risk to avoid right now is that mission creep, or moving of goalposts, described above. That is the reintroduction of lockdowns on the basis of small upticks in infection, leading to ever more of those diffuse but real harms, on the basis of unrealistic goals and increasingly implausible worst-case scenarios.

I am surprised to find myself in a contrarian position here, as I have also with some questions about food, discussed on this site. I might be wrong both times, but one has to just keep going where the evidence seems to lead.

___________

Notes on the notes:

* For an example of the kind of reasoning I find very hard to accept, consider this passage from a column in the New York Times, by John Barry, who wrote a book about the 1918 flu pandemic:

During the 1918 influenza pandemic, almost every city closed down much of its activity. Fear and caring for sick family members did the rest; absenteeism even in war industries exceeded 50 percent and eviscerated the economy. Many cities reopened too soon and had to close a second time — sometimes a third time — and faced intense resistance. But lives were saved.

Had we done it right the first time, we’d be operating at near 100 percent now, schools would be preparing for a nearly normal school year, football teams would be preparing to practice — and tens of thousands of Americans would not have died.

The US has long land borders with Mexico and Canada. Even if local suppression had been achieved in the US – with no significant hidden islands of infection – why does Barry think it would have been possible to go back to normal, in the absence of a vaccine?

** The more meaningful number is not total deaths per million but Covid-related excess deaths per million – deaths over and above what would normally have occurred over that time period. Or some similar statistic that takes into account normal mortality. Levitt’s twitter site currently has 3,800 excess deaths for Sweden, hence 380 excess deaths per million.

‡ I agree with this article in the Economist about the reopening of schools. This is an example of full consideration of the trade-offs.

______________

Hi Peter, I agree very much (and am also surprised to find myself in such a minority on this). A few comments:

1. I think the mission creep was there to begin with (so not so much a creep as a conflation, of goals). for instance, back in mid-March the NYT’s Daily podcast interviewed Andrew Cuomo who said things like “it’s about saving lives” and “it’s about making sure we live through this”. That stuck with me. He was not explicit but it was pretty clear he meant saving as many lives as possible, then worrying about the repercussions of lock-downs etc.

2. Levitt et al. published an article in the Israeli newspaper Haaretz (which has an English version, and may carry the article later this week, not sure). They spell out some of the claims you note. They argue, e.g. that because other coronaviruses have long been endemic, many people have partial or full immunity to the present virus. That’s way, they argue, you only need 20% of the population to get infected to get herd immunity, and that’s why you see the slowdown. (As an aside – Levitt has the bad habit of making precise numeric predictions without sufficient backup. Around March he argued on Israeli radio that no more than 10 people will die of the virus–its now in the mid 400s–and hat really damaged his reputation here).

3. One inchoate but persistent worry I have is that since many Western countries (esp. the U.S. but quite a few others) cope so badly with this pandemic, the Chinese model, as you might call it, will appear successful. It’s hard to tell of course, as this will take years to unfold. But if China also emerges from this in a fairly OK situation economically, I worry that many countries, especially developing ones, will learn the lesson that the kinds of measures imposed there are worth it, and this will legitimize (or at least make widespread) that kind of strategy of handling crises and of running things more broadly. I mean: lack of care for human rights and putting out conspicuous fires at the expense of long term effects. Does this sound overblown to you?

Your third worry is not something I’d thought about at all, and I agree entirely. That would be yet another bad outcome from all this.

Re 2: I will have a look at the Levitt paper in Haaretz — I think it is there. As you say, he has a surprising tendency to stick his neck out on numerical details, in a way that then can lead to trouble. He might have a Popperian attitude to this — make a prediction and see how it goes. But all he’d have to do is make more of a distinction between the rough picture and the fine details, and he’d be in a much better position. As it works now, he’s easy to write off entirely when a numerical claim goes awry, and that is what a lot of people would like to do.

p.s. I’d very much like to know of an alternative clearing-house for lockdown-skeptical information that is entirely scientific and not a product of conspiracy theories and the like. It would be good to have something else in addition to the Levitt site.

I tend to ‘worst case’ thoughts and currently I’m wondering what the world will look like if vaccines are ineffective(*) and herd immunity isn’t possible because the disease doesn’t cause sufficient immunity to keep the infection and death rates down. If this was a disease that just made most people sick for a few days, like the flu, then I think we can get to a point where we just accept a slight excess death rate along with a few days off. But this disease is really hard on many infected people resulting in ICU hospitalizations and long term effects that are only now being discovered. What then?

In any sane country, people would mask up, wash hands, stay apart, and buildings would be adapted to increase the air refresh rate. Here in the US, ‘sane’ behavior seems to be a distant dot on the horizon that is moving away from us. In the absence of rational behavior by the majority of the population and a lack of any government action, we seem to be stuck with ‘let them die’ or massive mandated lock-downs.

The (marginally) good news is that large corporations are implementing their own ‘no mask, no shop’ policies so, in the absence of intelligent government action, for profit businesses may be our last, best hope.

Stepping back, we’re early in this pandemic and the science keeps getting better so there may be other ways out of this mess. Fingers crossed and mask on.

(*) – http://theness.com/neurologicablog/index.php/herd-immunity-and-covid-19/

“In the absence of rational behavior by the majority of the population and a lack of any government action, we seem to be stuck with ‘let them die’ or massive mandated lock-downs.” Yes, and that is perhaps the most maddening feature of this situation, one aided now by political polarization. In Australia and the US, there is a strong association between attitudes to lockdowns and a broader left/right political divide. The right is fairly consistently looking for a lighter touch, and the left for a more stringent approach. (This is most evident in the media, but also in actual policy. I am not following the UK debates as closely, nb). This means that the general polarization of political life is feeding into disagreement about the lockdowns. I suspect that my defense of less stringent behavioral rules, and support for re-opening schools, will be seen as ‘right wing’ by many people, though I don’t think of it that way at all. And this is one of the things that result in a neglect of mixed or middle-path views.

“but one has to just keep going where the evidence seems to lead”

This is a very logical approach for a scientist or an academic such as yourself. However, few people on the planet can remain unaffected by the media-generated discourse and examine the numbers and charts. If one dares to mention issues such as education or human rights, he or she are immediately labeled as a conspiracist and ridiculed as such. The main problem is that binary thinking is enforced, you must either belong to the sane ones or to the idiots…No room for a third space, no room for discussion.

Sometimes I feel that there is nothing left to do but admire those octocorals and wait for some more of those beautiful shots…

Yes, and I think this is related to the tendency to think of attitudes to the lockdown as politically aligned – harder on the left, softer on the right. It’s hard to get past this distortion.