Earlier this week a special issue of the venerable journal Phil. Trans. R. Soc. appeared, with a collection of papers from a conference in London I went to back in March. The issue contains a paper by Gáspár Jékely, Fred Keijzer, and myself, which we started writing at an earlier conference (the subject of another post) at Tübingen in Germany last year.

Earlier this week a special issue of the venerable journal Phil. Trans. R. Soc. appeared, with a collection of papers from a conference in London I went to back in March. The issue contains a paper by Gáspár Jékely, Fred Keijzer, and myself, which we started writing at an earlier conference (the subject of another post) at Tübingen in Germany last year.

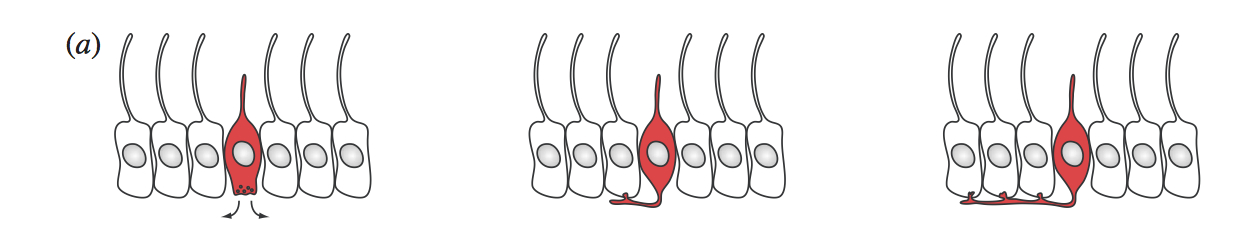

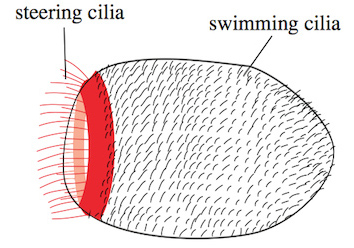

The aim of the paper is to chart an “option space” – an organized space of possibilities – for the early evolution of nervous systems. For me, the project stems from a paper published about five years ago by Gáspár, where he sketched a hypothesis about how nervous systems might have initially arisen and what they might have been doing. He worked through a sequence of possible evolutionary transitions in marine animals that sense their environment and move by means of cilia (little hair-like filaments on the outside of cells). The transitions are driven by increasing division of labor, and hence efficiency and precision, in the control of behavior by means of the senses.

For example, in tiny sponge larvae, goal-directed swimming is achieved by having a group of cells on the back of the animal that can both sense light and steer in response to it.

But once you’re doing that, there’s no need to have a sensor in every swimming cell; much can be gained by having a few cells specialize as sensors while many others specialize as swimmers. That requires some sort of connection between the two.

Signaling by a simple broadcasting of chemicals to any cell listening can achieve some of this, but it’s better still to have targeted connections between one cell and another. The result is a nervous system.

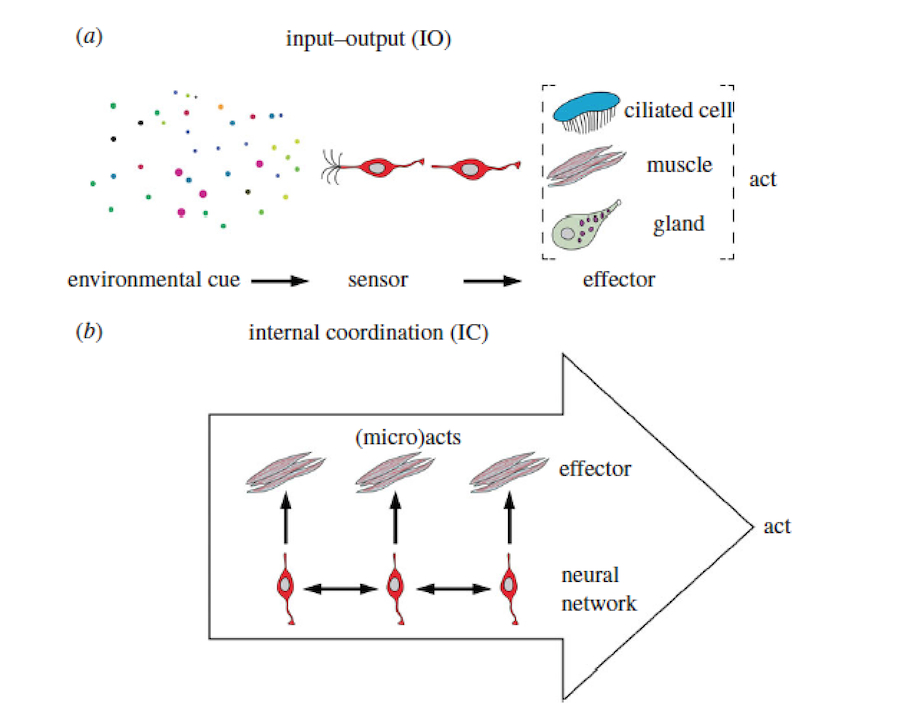

I met Gáspár when he gave a talk at a conference down in Washington DC. Not long after I saw a talk by Fred Keijzer at another event, where he used Gáspár’s work as an example of something he wanted to criticize, or at least question. As Fred sees it, many views in this area assume without argument a vision of the sort of role nervous systems play in the lives of animals. That vision is one in which the main function of nervous systems is dealing with information coming in through the senses and working out what to do in response. Fred, in a paper written with Marc van Duijn and Pamela Lyon, calls this the input-output model of what nervous systems do.

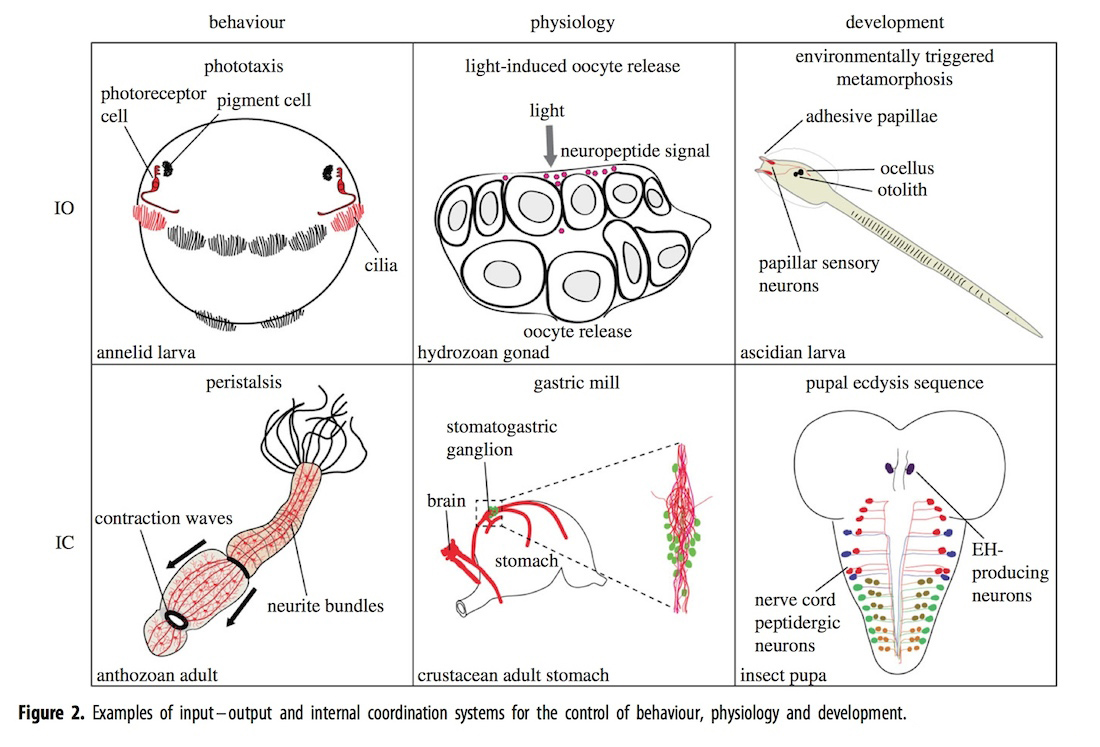

What else could nervous systems be doing? An alternative is often missed when people think about behavior in terms of a causal schema running from world, through senses, to internal processing, to action. What is missed is the difficulty of producing whole-body actions – producing them from the disparate activities of the many tiny parts that make up an animal. A neglected possibility, then, is that the role of the first nervous systems was mostly one of pulling the organism together, with respect to the creation of action. This can be called an internal coordination view of the function of early nervous systems. Here’s another figure from our paper, distinguishing these two different kinds of control.

Once the three of us started talking, it became clear that views like the one in Gáspár’s earlier paper occupy just one cell in a large space of possibilities, including many others that are neglected. In present-day animals, there are things other than behavior that nervous systems are used to control, especially physiology and development. And for all of those tasks – controlling behavior, physiology, and development – the kind of control being achieved might be of the input-output kind or the internal coordination kind, or a mix of the two. Hence the 2×3 table at the top of this post. For how these six options might relate to the historical sequence, have a look at the paper.

Once the three of us started talking, it became clear that views like the one in Gáspár’s earlier paper occupy just one cell in a large space of possibilities, including many others that are neglected. In present-day animals, there are things other than behavior that nervous systems are used to control, especially physiology and development. And for all of those tasks – controlling behavior, physiology, and development – the kind of control being achieved might be of the input-output kind or the internal coordination kind, or a mix of the two. Hence the 2×3 table at the top of this post. For how these six options might relate to the historical sequence, have a look at the paper.

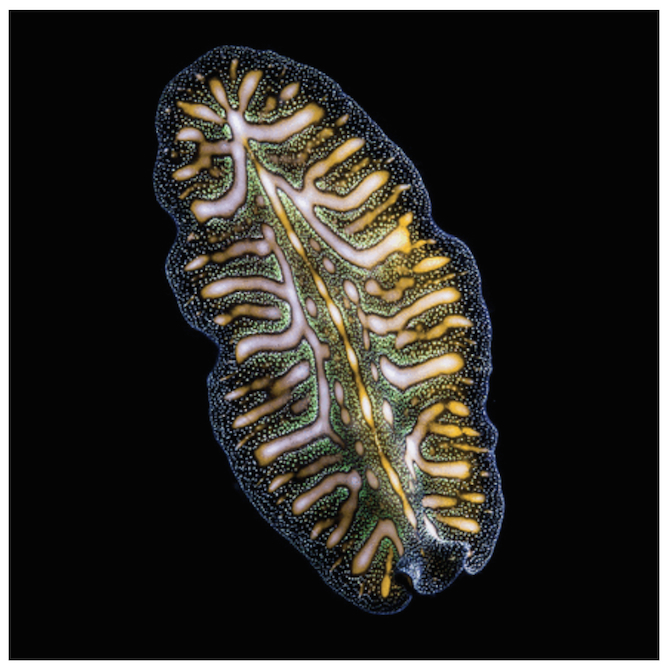

For the cover of this issue the editors chose an Australian platyhelminth (hence a relative of this animal from my Fiji collection). The species is Pseudobiceros bedfordi, AKA the “Persian Carpet Flatworm” (photo by Michael Bok). Everything in the issue, including our paper, is freely available until the end of November (after that, write to one of us for a copy).

Lastly, here’s a jet-lagged dawn photo of Chichely Hall, the country estate where the second half of the Royal Society’s conference was held.

________________

Notes: Gáspár drew the figures.